Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – Recent archaeological discoveries have provided new evidence supporting the accuracy of many Native American oral traditions. In particular, findings related to events described by English explorer John Smith (1580–1631) have shed light on historical interactions along the Rappahannock River in Virginia’s Northern Neck.

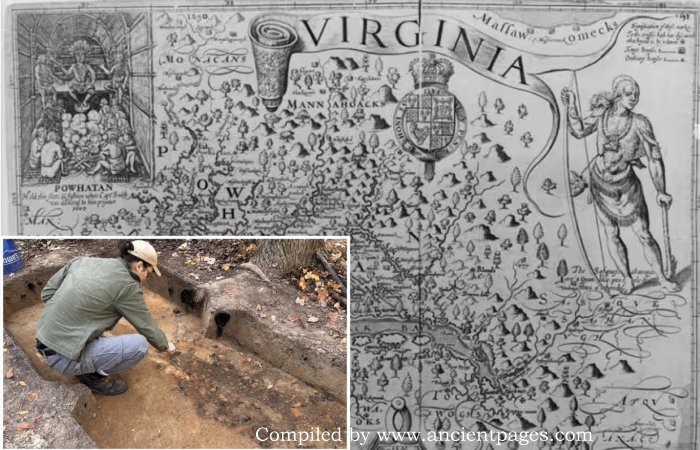

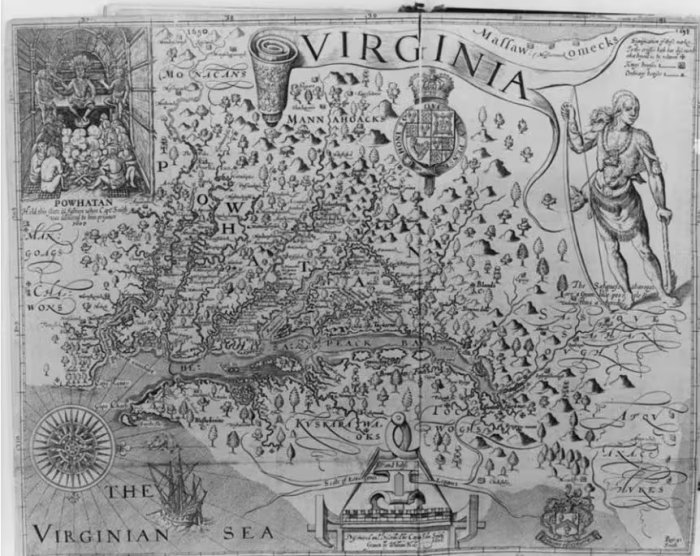

A map of Virginia in the early 1600s by the English explorer John Smith shows Native American tribes in the region. Credit: Library of Congress

John Smith’s 400-Year-Old Stories Confirmed

Smith, who mapped extensive areas of Virginia and New England and published influential travelogues, reported being attacked by Native Americans in this region during the 1600s. While historians have often questioned some of Smith’s accounts, new evidence is lending credibility to his reports.

A document from the 1660s records that the Rappahannock Tribe was promised 30 blankets in exchange for more than 25,000 acres of their land. Until recently, however, researchers had been unable to pinpoint the exact locations of these tribal towns.

The Rappahannock Tribe—officially recognized in 2018—has long asserted its historical presence and experiences in this area. As Chief Anne Richardson told the Washington Post, “Indian people have long known of the land and our history and presence here… But so often things aren’t considered ‘real’ until they’re found or ‘discovered.’ This validates what we’ve long known.” These findings not only confirm aspects of oral tradition but also highlight how archaeology can help bridge gaps between recorded history and indigenous knowledge.

The discovery resulted from several months of meticulous planning and dedicated effort. Professor Julia King, an anthropologist at St. Mary’s College of Maryland, led a team that combined historical research with local knowledge by cross-referencing historic maps, documents, and deeds alongside oral histories from Rappahannock tribal members. In the fall, they began excavations in Richmond County near the bluffs.

Their efforts were rewarded when they uncovered as many as 11,000 artifacts at Fones Cliffs—an area historically inhabited by a Virginia tribe documented by John Smith. The findings included tiny beads, intricately marked pottery shards, stone tools, and pipes. These artifacts provide tangible evidence confirming the existence of Rappahannock towns and villages described in early colonial records.

King first began studying the Rappahannock Tribe’s history in 2016 at the request of the National Park Service’s Chesapeake Bay Office, the Chesapeake Conservancy, and the Rappahannock Tribe. The work was undertaken to provide interpretive support for the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. Following that project, King, her students, and the Rappahannock Tribe have continued their collaboration and discovered literal pieces of the Tribe’s past.

Scientists discovered the villages by combining historical research and local knowledge, cross-referencing maps, documents, and deeds with oral histories from Rappahannock tribal members.

Credit: Julia King

“Archaeology can deepen, confirm, and complicate what the oral history and historical documents relate about these past places,” Professor King said.

In this instance, the thousands of artifacts discovered have confirmed the Tribe’s historical sources. King said while many are excited to highlight the find, she is eager to highlight the students in the field conducting the research.

“Our students, whether they stick with the project beyond graduation or not, have contributed to finding answers to real-world questions,” she said in a press release.

Rappahannock Tribe’s Long Journey To Reclaim Ancestral Land

As of now, the Rappahannock Tribe has successfully reclaimed approximately 2,100 acres of its ancestral land. Historically, during the tribe’s height in the mid-to-late 1500s, their territory spanned more than 350,000 acres along the river valley and supported a population of nearly 2,400 individuals.

In 1608, Smith and his team departed from Jamestown to chart the Chesapeake Bay. While navigating the river by boat, they were observed by members of the Rappahannock Tribe from nearby cliffs. Meanwhile, other Indigenous people concealed themselves in marshes—armed with arrows and camouflaged as bushes—preparing for an ambush as Smith’s party approached a narrow section of the river. Although Smith and his men ultimately escaped unharmed, this encounter is notable; Smith later included several Rappahannock towns at Fones Cliffs on one of his most renowned maps of the region.

Artifacts found at the Fones Cliffs archaeological dig. Credit: Julia King

“We had heard the Indigenous stories of towns on the cliffs, and we had seen John Smith’s map showing three towns up there, but we had not found artifacts supporting that until now,” said King, who, with the tribe’s blessings, led the work at Fones Cliffs.

The Rappahannocks, with support from donors, government agencies, and conservationists, have worked in recent years to reclaim their ancestral homelands. This effort reflects a growing national movement to return land to Native American tribes as a form of restitution.

See also: More Archaeology News

“These are people who were displaced from their land more than 400 years ago, and it’s so important that they’re given the opportunity to regain that connection that by right is theirs,” said Heather Richards, the Mid-Atlantic regional vice president for the Conservation Fund, which helped the Rappahannocks acquire a large parcel of land at Fones Cliffs.

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer