Yves here. A vignette provides confirmation of Vietnam’s fierce retention of its identity during the period of Chinese rule. In the documentary The Fog of War, a not-exactly-satisfactory effort at atonement by former US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, he recounts how, many years after the Vietnam War, he was able to arrange a dinner with the leaders of North Vietnam during the conflict.

Needless to say, it was a pretty tense affair. Finally, one of the North Vietnamese officials asked: “Why did you go to war with our country?”

McNamara invoked the domino theory, that if North Vietnam won, China and Chinese communism would advance across Southeast Asia.

McNamara reported that his counterparts nearly leaped across the table: “How could you go to war understanding so little about our country? We spent 1000 years expelling the Chinese.”

Readers likely have much more data or anecdata about countries that disappeared and then revived due to strength of identity, as opposed to, imperialistic utility.

By Lorenzo Hofstetter, an independent researcher and co-creator/COO of the Phersu Atlas database (2022). He holds a degree in archaeology from the University of Florence and collaborates with journals in Italy and Switzerland. In 2023, he curated the exhibition Cacao entre dos Mundos at the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence, Italy, and in 2025, published Colonial Florence with the CAPASIA Project at the European University Institute. His research focuses on historical cartography, cultural history, and world history. Produced by Human Bridges

Global political history is punctuated by state entities that, after vanishing from the international stage, have reemerged in new forms—sometimes radically transformed, sometimes strikingly faithful to their origins. These revived states—polities that have undergone phases of dissolution, fragmentation, or annexation before regaining effective sovereignty—offer a privileged lens to examine the intermittent nature of statehood. Far from being a permanent attribute, sovereignty reveals itself as a fluctuating condition, subject to temporary suspensions, territorial redefinitions, and identity reactivations.

I co-developed a digital mapping tool called Phersu Atlas between 2020 and 2025, which enables navigation through tens of thousands of states spanning from 3499 BCE to 2025 CE. Its use allows for the possibility of identifying recurring patterns and dynamics that illuminate the problem of intermittent statehood with precision.

To illustrate, I’ve chosen the cases of Armenia, Vietnam, and Poland. These existing states share a history marked by porous borders, subjugation to external powers, and a resilient identity. Through the analysis of time series data on population and territorial extent, as well as the infographics and interactive maps provided by Phersu Atlas, the aim is to explore the dynamics of state suspension and reemergence, highlighting the conditions under which latent sovereignty can once again materialize as a recognized political entity.

These cases do not merely represent a return to sovereignty, but rather full processes of identity and institutional reactivation. The rebirth of the state entails the reconstruction of borders, symbols, and shared narratives—often in contexts of deep geopolitical instability. The ability of people to transform historical memory into a political project is what distinguishes mere cultural survival from true state revival.

In approaching these three historical cases, one can already identify recurring factors that have played a crucial role in preserving identity. Notably, the early development of a national language (accompanied by a robust literary tradition), the adoption of a distinct religion, and the frequent recourse to acts of explicit rebellion are common traits found among all states that have experienced a historical “revival.”

Despite centuries of foreign domination and political fragmentation, Armenia, Vietnam, and Poland have preserved their national identities through a strong continuity of culture. Language played a central role in this process: Armenian, with its unique alphabet created in the fifth century, cemented the cohesion of the people even during its diaspora; Vietnamese, though influenced by Chinese, retained its own phonetic structure and an autonomous writing system—first through Sino-Vietnamese characters, later through an adapted Latin alphabet; Polish, having survived the partitions and even after being banned in certain regions, remained the vehicle of literature.

Writers such as Juliusz Słowacki and Zygmunt Krasiński composed works that not only preserved the Polish language but also nourished the national imagination. Polish Romantic poetry became a tool of resistance, capable of keeping the idea of a homeland alive even in the absence of a state.

Literary and philosophical production served as a guardian of memory: from Armenian epic poems to Polish patriotic verse to Vietnamese Confucian texts, each culture found refuge and a form of resistance in the written word. In all three cases, religion further reinforced identity: Apostolic Christianity in Armenia, Buddhism and ancestor worship in Vietnam, and Catholicism in Poland. These elements functioned as invisible pillars, capable of sustaining the nation even when the state itself had ceased to exist.

In the process of cultural survival that accompanied the disappearance and reappearance of the state in Armenia, Vietnam, and Poland, certain literary works acted as true bastions of ethnic identity, capable of preserving memory and reinforcing a sense of belonging. In Armenia, The History of the Armeniansby Movses Khorenatsi, composed around the mid-fifth century (circa 440–470 CE), provided an organic narrative of the Armenian people’s origins, weaving together myth, genealogy, and history in a text that withstood Persian, Arab, and Ottoman dominations. In Vietnam, the poem The Tale of Kiềuby Nguyễn Du, written between 1813 and 1820, embodied the cultural soul of the nation during a period of transition and vulnerability, elevating the Vietnamese language and Confucian values as symbols of moral and identity-based resistance. In Poland, Pan Tadeusz by Adam Mickiewicz, published in 1834 in Paris during the author’s exile, represented an act of nostalgia and imaginative reconstruction of the lost homeland, strengthening the Polish language and national sentiment at a time when the state had been erased from the map.

Armenia, Vietnam, and Poland have each expressed, throughout their histories, a tenacious will for national emancipation, manifested through patriotic movements rooted both in antiquity and modernity. In Vietnam, as early as ancient times, the famous rebellions of the Trưng sisters (40–43 CE), who led an uprising against Chinese domination, and that of Lady Triệu in 248—a heroic figure who defied occupation with strength and charisma—stand as foundational episodes deeply embedded in the collective memory. These events foreshadow a long tradition of resistance that culminated in the 20th century with Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh, which spearheaded the struggle against French colonialism and later against American intervention during the war of reunification.

In Armenia, resistance took various forms: from medieval uprisings against Arab and Seljuk rule to the nationalist movements of the 19th century, such as the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (“Dashnaktsutyun”), which fought for independence in 1918 and later against Sovietization.

In Poland, the insurrectionary tradition is equally profound: from the uprisings against the Russian Empire in the 19th century (1830 and 1863), to the heroic Warsaw Uprising of 1944 against Nazi occupation, and finally to the “Solidarność” movement of the 1980s, which led to the fall of the communist regime in 1989. In all three cases, rebellion was not merely a political response but a profound expression of national identity.

Armenia—Intermittent Sovereignty and Ancient Imperial Echoes

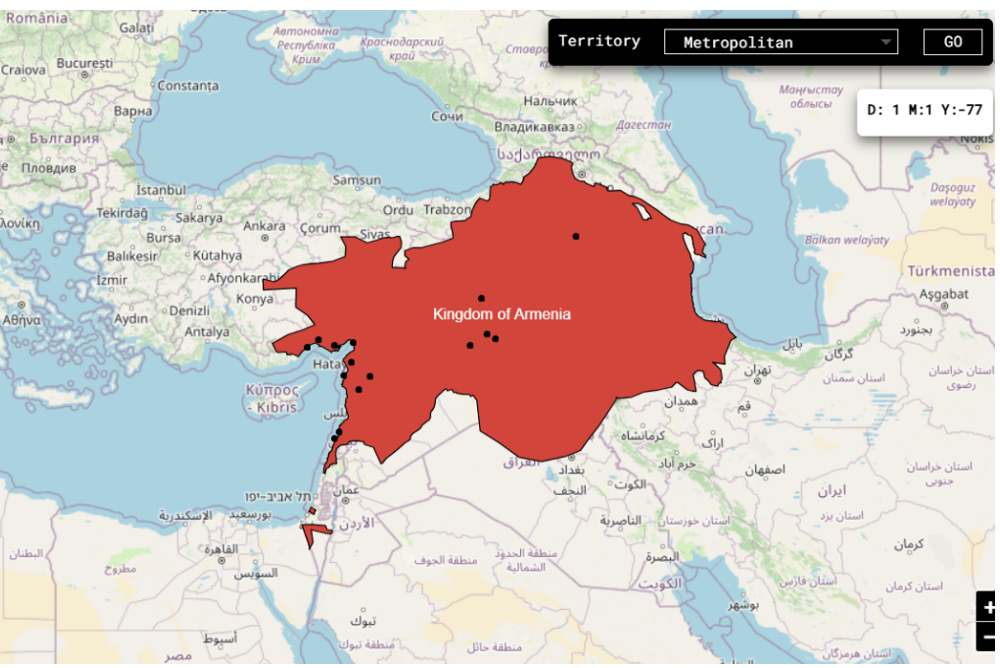

The case of Armenia stands out for its historical depth and the multiplicity of its state incarnations. From the ancient Kingdom of Urartu (860–585 BCE) to its reincarnations as the Kingdom of Armenia (321 BCE–428 CE) and the curious “exiled polity” represented by the Kingdom of Armenian Cilicia (1078–1375), the territory has continuously passed under Persian, Seleucid, Roman, Arab, Byzantine, and Ottoman dominations. At the height of its territorial expansion, in 77 BCE, ancient Armenia appeared as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Territorial projection of the Kingdom of Armenia at its zenith in 77 BCE, illustrating the spatial foundation upon which later claims to sovereignty and identity would be constructed.

Armenia subsequently experienced a condition of intermittent sovereignty, in which statehood alternated with long periods of foreign subordination. This process is clearly illustrated in a graph depicting the area of ancient Armenia, where the periods of subjection to other entities are distinctly visible (Figure 2). Despite territorial fragmentation and the absence of a unified state for centuries, Armenian identity remained alive through its language and Christian religion (adopted as the state faith as early as 301 CE).

Contested for centuries by Romans, Parthians, Byzantines, and Arabs, Armenia was reborn as a kingdom in 886 thanks to the intervention of King Ashot (890 AD). On that foundation, the Armenian people would later develop further aspirations for unity, though they were subsequently subdued by the Seljuks (1045–1200), the Mongol Ilkhanate (1236–1335), the Ottoman Empire (1514–1828), and then the Russian Empire (1828–1917). The founding of the Republic of Armenia in 1918 and its rebirth in 1991, following the final collapse of the Soviet Union, represent moments of sovereign reactivation, in which latent statehood was transformed into a recognized political entity.

Figure 2. Temporal graph of Armenia’s fluctuating sovereignty, highlighting the alternation between autonomous rule and foreign domination. The dataset reflects both ancient and modern clusters, underscoring the longue durée of Armenian statehood.

More than other cases, Armenia demonstrates that statehood is not a continuum, but rather an oscillation between presence and absence and between power exercised and power imagined. Moreover, the Armenian people share the traumatic experiences of diaspora and genocide with the Jewish people (perpetrated by the Turks between 1915 and 1923)—elements that, paradoxically, seem to catalyze unifying ambitions and reinforce the desire to restore an Oikos for their Ethnos. (Oikos in Ancient Greek refers to the fundamental domestic unit, encompassing the family, property, and internal economic relations; Ethnos instead designates a human group united by language, culture, and traditions, often in contrast to external groups.)

Vietnam—A Suspended State Through the Millennia

The history of Vietnam is marked by a recurring alternation between moments of sovereignty and phases of subjugation. This is clearly visible in the graph in Figure 3, where—compared to the previous Armenian case—one can appreciate the great variability and frequency with which the Vietnamese state has undergone foreign occupations. It is all the more interesting, therefore, to compare this graph with the one depicting the times China has invaded Vietnam throughout history (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Chronological visualization of Vietnam’s intermittent sovereignty, revealing the cyclical nature of its political autonomy and the frequency of external subjugation across two millennia.

Figure 4. Historical mapping of Chinese incursions into Vietnam, disaggregated by dynastic clusters. The graph emphasizes the persistent geopolitical tension and the role of invasion in shaping Vietnamese state formation.

The emergence of the kingdom of Nam Việt as early as 207 BCE represented the first form of autonomy. But this was soon interrupted by the first Chinese domination, which inaugurated a long series of imperial subjugations starting in 111 BCE. Brief interludes of rebellion, such as that of the Trưng sisters (Figure 5), occurred within a continuum of successive dominations: the second (43–544), the third (602–905), and the fourth (1407–1427), interspersed with episodes of ephemeral or partial independence. True independence was consolidated in 938 with Ngô Quyền’s victory on the Bạch Đằng River, marking the beginning of a period of sovereignty that withstood even the Mongol invasions of the 13th century.

Figure 5. Geospatial reconstruction of the Trưng sisters’ uprising (40–43 CE), offering insight into early female-led resistance and the territorial scope of proto-national mobilization against imperial rule.

However, from the 16th to the 19th century, Vietnam entered a phase of internal fragmentation, marked by the coexistence of rival dynasties and increasing geopolitical vulnerability. The French domination (1887–1953) marked a renewed loss of sovereignty, further aggravated by the brief Japanese occupation in 1945. Only through the long war of independence (1955–1975), culminating in postwar reunification, did Vietnam regain full statehood, reactivating a sovereignty that, although more recent, is rooted in a long memory of resistance and resurgence. Particularly interesting, relating to the centuries-long history of the Vietnamese state, is the ranking of major geopolitical changes triggered in a wartime context (Figure 6). Figure 6 is especially relevant as it illustrates how war, despite its destructiveness, often acts as a catalyst for territorial redefinition and the resurgence of Vietnamese sovereignty. Each conflict marked in the chart represents not only a crisis but also an opportunity for the consolidation of national identity and the reaffirmation of statehood.

Figure 6. Comparative ranking of major conflicts affecting Vietnam’s territorial integrity, illustrating how warfare has historically functioned as a vector of both fragmentation and sovereign consolidation.

Poland—The Quintessential Revived State

Poland represents one of the most emblematic examples of a revived state in the modern era. Following the three partitions of the 18th century (1772, 1793, and 1795), the country formally disappeared from the European map for more than a century, having been absorbed by the Russian Empire, Prussia, and Austria. Nevertheless, the cultural, linguistic, and religious continuity of the Polish population—combined with the persistence of insurrectionary movements and national literary and historical production—kept alive the idea of suspended sovereignty.

In this sense, 19th-century Poland can be interpreted as a latent state, lacking legal recognition but active in the symbolic and identity spheres. The restoration of statehood in 1918, at the end of World War I, marked the return of effective sovereignty, which would again be challenged during World War II and the Soviet era. Poland thus embodies a cyclical nature of statehood, where legal death does not equate to political extinction, and where the reemergence of the state is the result of a long cultural and geopolitical gestation.

Figure 7. Cartographic chronology of territorial integration within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, tracing the expansion of a composite sovereignty across Central and Eastern Europe.

The history of Poland is a succession of assertions of sovereignty and dramatic interruptions. Beginning in 966 with the Christianization of the duchy, the first political identity took shape and was consolidated in the Kingdom of Poland (1026–1385). This personal union with Lithuania marked the start of a phase of expansion and prestige, culminating in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth of 1569—one of the largest political entities in early modern Europe (Figure 7). However, between the 18th and 19th centuries, Poland underwent three partitions (Figure 8), which erased its statehood for more than a century.

Figure 8. Post-partition map of Central Europe (1796), depicting the geopolitical erasure of Poland and the redistribution of its territory among imperial powers—a visual testament to the fragility of state borders.

Only in 1921, with the Second Republic, did the country regain its independence, which was threatened and ultimately extinguished by Nazi occupation during World War II (Figure 9). After the war, Poland was reborn as a People’s Republic in a context of sovereignty limited by Soviet influence. It was only in 1989, with the end of the communist regime, that Poland reemerged as a fully independent state, reactivating a tradition of autonomy that, although interrupted multiple times, was never definitively broken.

Figure 9. Temporal map of Nazi occupation in Poland (1939–1945), distinguishing between directly annexed zones and the General Government. The visualization reflects the gradations of control within a context of imposed sovereignty.

Intermittent Statehood Today

The revived state is a form of intermittent sovereignty, in which statehood reemerges after a phase of latency, suspension, or denial, sustained by the persistence of a collective identity and the reactivation of political memory. This concept has often been discussed and analyzed by various scholars. Starting with Andreas Zimmermann (1961), professor of International and European Law at the University of Potsdam, Germany, who has written extensively on the continuity of the state in international law. It becomes evident that sovereignty can survive the loss of territorial control or the suspension of governmental functions, maintaining a legal latency that allows statehood to reemerge under favorable conditions. Sociologist Charles Tilly (1929-2008), on the other hand, interprets statehood as the product of historical processes of coercion and capital accumulation, suggesting that the revived state is not a mere return, but a new configuration of political power, often generated by conflict and social mobilization. From this perspective, state revival is not a simple return to the past, but a new configuration of political power, often born out of social mobilizations and economic transformations. Intermittent sovereignty thus becomes a form of historical adaptation, where the memory of the past merges with the present and needs to generate new forms of legitimacy.

Historian Benedict Anderson (1936-2015) offers a contrasting cultural interpretive approach: the persistence of an imagined community can serve as an identity substrate that survives the formal dissolution of the state, making its rebirth possible as an expression of a collective will that is reactivated over time. In this sense, the revived state embodies an intermittent sovereignty, capable of reemerging thanks to the tenacity of political memory and the resilience of the symbolic structures that sustain it.

The analysis of revived states invites us to rethink statehood not as a permanent condition, but as an intermittent phenomenon, subject to cycles of emergence, suspension, and reactivation. Sovereignty, far from being a stable attribute, is configured as a tension between exercised power and latent powerand between legal recognition and historical memory. The cases of Armenia, Vietnam, and Poland show how statehood can survive conquest, fragmentation, and diaspora. But there are also cases in the 21st century that represent fertile ground for hypothetical and not entirely improbable future developments.

By studying the clusters related to the multiple historical manifestations of Kurdistan and Arakan, it is possible to observe how future statehood is already inscribed in the present, in the form of aspiration, mobilization, and alternative cartography. This inscription of the future within the space of the present is not merely an ideological projection, but a concrete practice manifested through self-governance structures, emerging national symbols, and new narratives. In Kurdistan and Arakan, sovereignty is not a legal status but an evolving process, sustained by networks of solidarity, local institutions, and a shared territorial vision. These elements constitute a form of “pre-statehood” which, though lacking international recognition, already functions as a political and cultural infrastructure.

The Kurds, living in the Middle East since antiquity, saw the possibility of an autonomous state fade with the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, which was replaced by the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, ignoring Kurdish claims. In 1946, the short-lived Republic of Mahabad was founded in Iran, while in Iraq, the Regional Kurdistan gained autonomy in 1991 and held a referendum for independence in 2017. In Syria, the region of Rojava has experimented with forms of democratic self-government since 2012.

Figure 10. Spatial evolution of Kurdish territorial control in Syria during the civil war (2011–2024), illustrating the emergence of autonomous governance structures within a fragmented national framework.

Arakan, on the other hand, traces its roots to the Kingdom of Mrauk U (1430–1784), which was conquered by the Burmese in 1784 and ceded to the British in 1826. As of 2025, the armed group Arakan Army exercises de facto control over large areas of western Myanmar, with a parallel governance structure that challenges central authority. In both cases, the possibility of future state emergence depends on the ability to consolidate local institutions, maintain popular support, and navigate complex regional dynamics, while balancing historical memory with political pragmatism. In this sense, the study of revived states is not merely a historiographical exercise, but a reflection on the very nature of political power, the resilience of collective identities, and the shifting geography of sovereignty—with significant implications for contemporary geopolitics.

Figure 11. Projected territorial extent of Arakan Army control in 2025, signaling the consolidation of parallel sovereignty and the potential trajectory toward formalized statehood.

Dynamic visualization of territorial changes ensures an immediate grasp of sovereignty’s fluctuations over time. Through interactive maps and historical series, one can observe not only phases of expansion and contraction but also unstable border zones, overlapping jurisdictions, and contested areas. This cartographic approach enriches our understanding of global history, turning political geography into a visual and analytical narrative.

Additional Reading:

- Anderson, Benedict, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Verso Books, London (2006).

- Khorenatsi, Movses, History of the Armenians, Harvard University Press, Cambridge (2006).

- Mickiewicz, Adam, Pan Tadeusz: The Last Foray in Lithuania, Penguin Classics, London (1995).

- Nguyễn Du, The Tale of Kiều, Yale University Press, New Haven (1987).

- Tilly, Charles, Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990–1992, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford (1992).

- Zimmermann, Andreas, “Continuity of States,” Max Planck Encyclopedias of International Law (2006).

Visual Data and Mapping: