John Muir officials would not comment on the incident, citing privacy laws. But in an email, Ben Drew, a spokesperson for the hospital, said general policy is that “If a law enforcement agency indicates that visitation presents a safety or security concern, [the hospital] may limit or deny visitation to protect our patients, staff, and visitors.”

Saidi said that when the wife insisted on getting information about the man’s condition, hospital security called the police.

“We understand that emotions are high whenever a family member or friend is in the emergency department or hospital,” said Drew. “The hospital only involves local police in circumstances when a patient or visitor’s behavior becomes abusive, disruptive, or threatening, and cannot be resolved through our own security team.”

Saidi denied that the family was being disruptive, saying that conversations with hospital staff and administration were respectful and no voices were raised.

“The atmosphere in that emergency bay was something like I’ve never seen before in my career,” Saidi said. “There was a chilling effect. Everyone was averting their eyes. You could tell the staff felt bad.”

Multiple emergency department nurses told Mobeen, a local California Nurses Association leader at John Muir, that ICE officers were “very aggressive with staff” and staff were afterwards “emotionally and physically upset” by what happened, she said.

“It’s horrifying to not be able to tell patients’ family members how they are, what their status is,” Mobeen said.

Part of the issue, Mobeen added, is training. Staff were not given adequate training on how to respond to any kind of immigration enforcement action that may occur at the hospital, she said.

Drew, the spokesman for John Muir, countered that the hospital has given guidance on its longstanding law enforcement policy and answered multiple questions since January about what to do if ICE agents show up at their facilities.

Limits for ICE access, sometimes murky

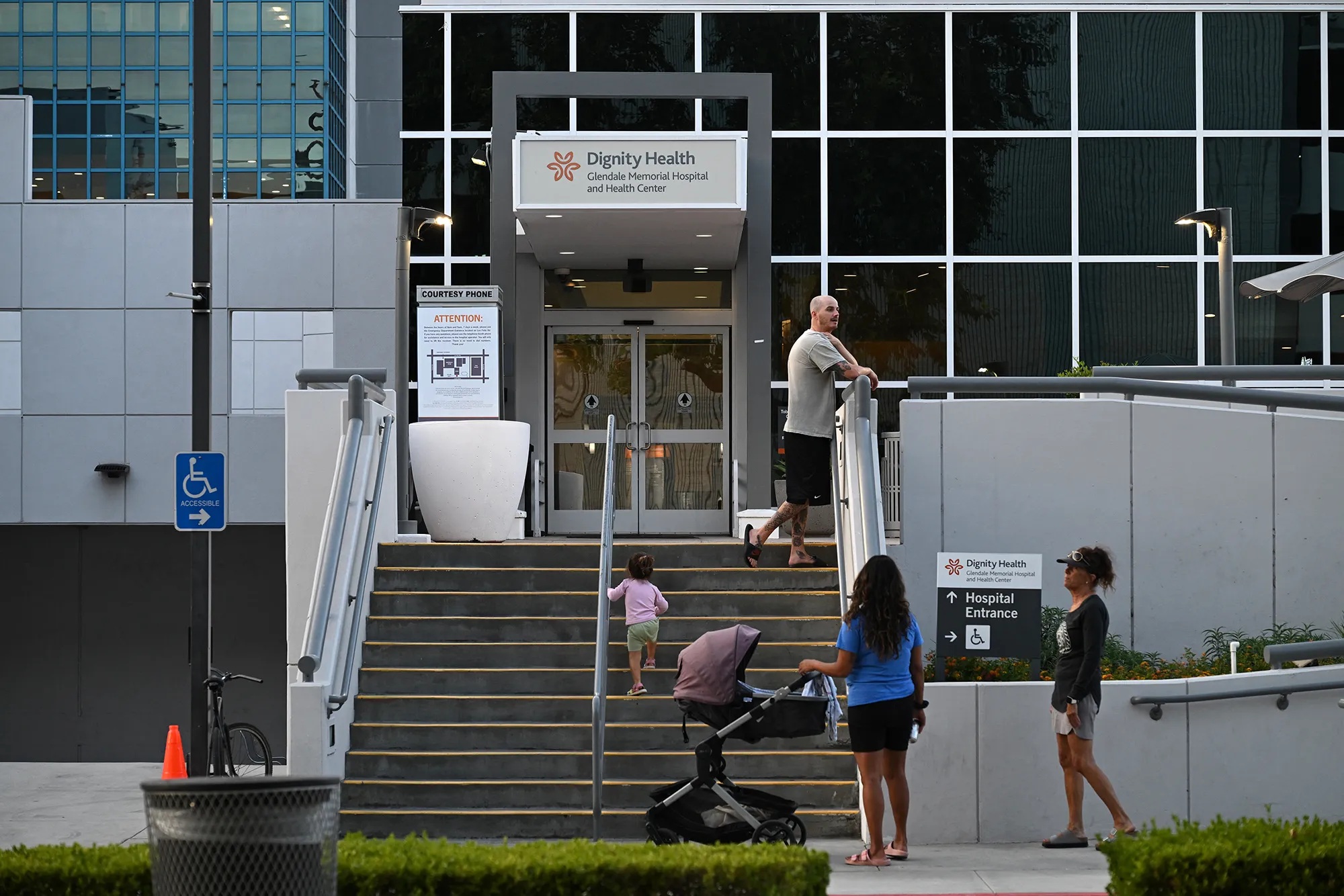

Last month, immigration agents occupied the lobby of Dignity Health’s Glendale Memorial Hospital, even standing behind reception desks, as photos that circulated online showed. Protestors gathered outside the hospital, hosting rallies and press conferences.

They were all there because agents had previously brought in Milagro Solis-Portillo, an immigrant from El Salvador, for medical care following her detention. They spent 15 days in the hospital waiting for Solis-Portillo’s discharge before transferring her to another hospital and then taking her into custody, according to local news reports.

In a statement, officials from Dignity Memorial Hospital said they could not legally prohibit law enforcement from being in public areas.

That’s true, say legal experts: Waiting rooms and lobbies are considered public spaces in hospitals. But agents cannot move through hospitals without limits. Law enforcement officials are not allowed to search for people in exam rooms or other private spaces without a federal court warrant.

When agents bring in someone who is in their custody and needs medical care, the application of the law can be more murky.

According to Richardson at the hospital association, how far an agent can go into treatment areas with a detained patient may be decided on a case-by-case basis. In cases where a detained patient is struggling or resisting, that patient may need guarding, she explained.

And if law enforcement officers do go inside exam rooms, they may hear medical information while on guard. But that isn’t necessarily a privacy violation, according to federal rules. The HIPAA Privacy Rule, the law that sets privacy standards for medical information, has a provision that allows for “incidental disclosures” of information as long as “reasonable safeguards” are applied.

“The hospital will, and the doctor will make reasonable attempts to protect the patient’s privacy.” “What is reasonable is going to depend, again, on what’s wrong with the patient, how the patient is behaving, the nature of the circumstances,” Richardson said.

HIPAA protects the disclosure of medical records, which include names, addresses and social security numbers along with health conditions. State law also requires health facilities to protect this information. According to guidance from the attorney general’s office, health facilities should consider a patient’s immigration status confidential.

At the same time, some disclosures are required if law enforcement can prove lawful custody or show an appropriate warrant. A federal court warrant signed by a judge grants law enforcement immediate access to information or to search a particular area, while an ICE administrative warrant does not require immediate compliance.

Health workers in ‘precarious’ situations

Health facilities generally direct frontline workers not to engage with immigration agents, but rather to immediately contact security or management.

One particular incident at a Southern California surgery center stands out, in conversation with health workers.

On July 8, federal agents targeted three landscapers who had parked outside of the Ontario Advanced Surgical Center. They chased one of the men inside on foot, according to a felony criminal complaint filed against two health care workers in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California.

In videos of the incident posted online, a masked agent wearing a vest labeled “POLICE ICE” on the back holds a weeping man by the shoulder inside the center while several workers in scrubs stand by. At multiple points in the video workers ask the officer for identification; one worker says, “this is a private business.”

Two workers, Danielle Davila and Jose Ortega, tell the officer to leave. Davila moves between the officer and the man, saying “Get your hands off of him. You don’t even have a warrant.”