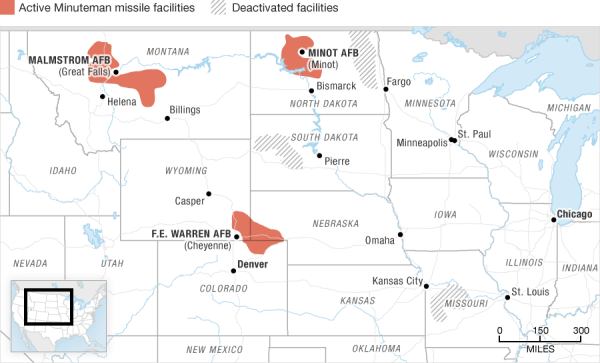

There are 400 nuclear missile silos in the central United States that constitute the land-based component of the U.S. nuclear deterrent. The Minuteman III missiles in the silos are roughly 50 years old. Although they have been repeatedly upgraded over the years, the Air Force decided a replacement should be developed. The new missile under development, the Sentinel, has turned into a classic case of a mismanaged weapons program.

Minuteman missile in silo – time to retire?

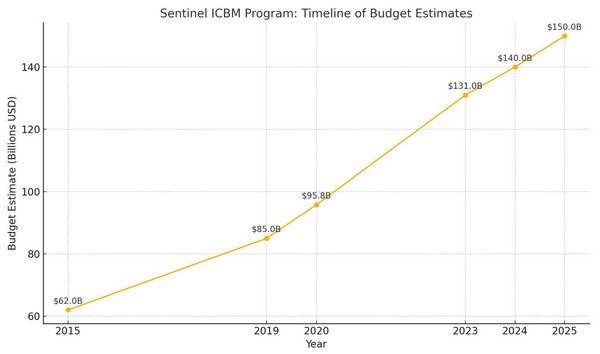

The initial concept of the Sentinel missile program was to directly replace the Minuteman III missiles in the existing launch silos. By reusing the silos, the project was made cost competitive with the alternative of another life extension for Minuteman or a switch to a mobile missile concept. Although at the start Boeing and Northrup Grumman competed for the contract, Boeing withdrew in 2019 and Northrop became the sole bidder. Projected costs began to climb sharply after this point and in January, 2024, the Air Force notified Congress that the Sentinel program’s costs had exceeded baseline projections by more than 25%, constituting a critical Nunn-McCurdy cost limit breach. This breach mandated a formal review and certification process to determine whether the program should continue.

In July of 2024, the Department of Defense completed its Nunn-McCurdy review. The Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment certified that the Sentinel program met the necessary criteria to proceed. However, he rescinded the program’s Milestone B approval and directed a restructuring to address cost overruns and management issues. It remains to be seen whether Northrup Grumman will make substantial changes to curtail the cost of the program.

Digging for Dollars

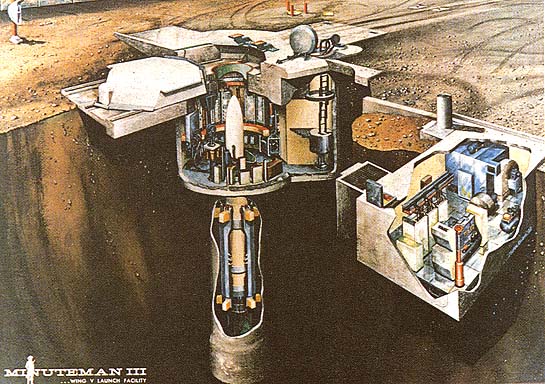

The most remarkable development in the course of the runaway cost estimates for the Sentinel missile is the recent decision to build new silos instead of reusing the existing ones. In May 2025, the U.S. Air Force announced that the Sentinel ICBM program would require the construction of entirely new missile silos, adding billions to the cost of the project. This decision was made after assessments revealed that the aging Minuteman III silos, some approaching 100 years old by the end of Sentinel’s expected service life, could not be adequately adapted for the new missiles. Factors such as structural degradation and the need for extensive modernization were the basis of the determination that building new silos was more practical and cost-effective than retrofitting the old ones.

Minuteman silo complex – too hard to fix?

Asserting that “structural degradation” has occurred in reinforced concrete structures designed to survive a near-miss by a nuclear weapon is puzzling to say the least. Moreover, the notion that modern fiber optic linked control infrastructure could not be retrofitted in structures accommodating far bulkier analog cabling and old electronic systems is highly questionable. In addition, there is a fundamental concern regarding silo construction: modern nuclear missiles are accurate enough to destroy even the most robustly constructed silo. The accuracy of ICBMs is now within 30-50 meters of a target. There is no feasible silo design that can survive a near hit (within 100-200 meters) by a modern earth-penetrating nuclear warhead. This makes attempts to improve on the hardening of existing silos pointless. The survivability of missile silos is now largely a myth sustained by institutional inertia and defense contracting incentives.

Minuteman missile site locations

The Mischievous Magic of Nuclear Deterrence

Perhaps the greatest boon conferred on the defense industry by the nuclear era is the elusive concept of deterrence. Like Schrodinger’s cat, it exists concurrently in two contradictory states. It is always absolutely vital, yet perennially insufficient. Its advocates maintain that it is working faultlessly because we have been spared nuclear attack, while simultaneously maintaining that we are in imminent danger of losing deterrence unless we spend large sums to preserve it. The magical property of deterrence is that there is no measurable connection between money spent on deterrence and the corresponding amount of deterrence secured. This is because deterrence exists in the minds of potential attackers, whose psychology is unknown and unknowable. Yet deterrence is deemed so important that it functions as a major justification for any new nuclear weapons program. The deterrence argument has become a fountain of riches for the makers of strategic nuclear weapons.

Magical thinking about deterrence is abundantly displayed in the dubious design decisions of the Sentinel missile program. Originally intended as a simple replacement for the ageing Minuteman III land based missiles, Sentinel has turned into a runaway weapons program, with projected costs greatly exceeding initial estimates. Sentinel program advocates invoke the magic of deterrence as justification for every costly feature added to the missile. They argue that a bigger payload, longer range, and more survivable silos will all add to deterrence, so why should we quibble over another hundred billion dollars?

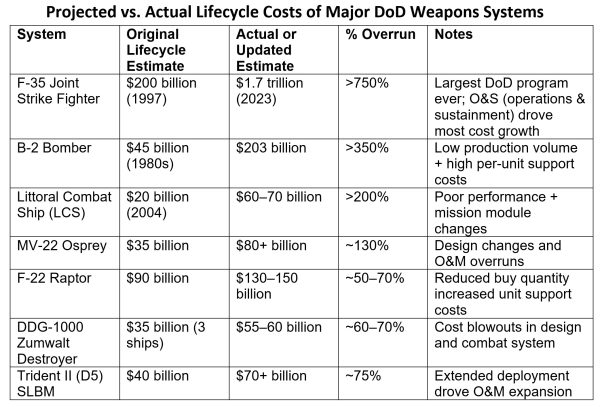

Development Risk vs. Development Grift

There is a legitimate argument for accepting risk in weapons development if the goal is a quantum leap in capability. The development of stealthy combat aircraft provided a measurable military advantage over potential adversaries, and thus cost and schedule overruns of these programs could be defended to some degree. However, the Sentinel program, like several other mismanaged U.S. weapons programs, does not deliver a significant new capability but provides dubious “improvements” at enormous expense. Defense contractors, military leaders, and politicians all have incentives to overstate the value of such programs and understate their costs, knowing that once started the momentum of a big weapons project is hard to stop. This problem does not end with the development of the weapon. The grift that keeps on giving is the lifecycle cost, the cost of supporting a weapon system during its operational lifetime. This cost is also chronically underestimated, and the main beneficiary is again the defense contractor. There is reason to believe that Sentinel will follow this pattern and have lifecycle costs exceeding current estimates of $250-$300 billion.

Conclusion

The Sentinel missile program is yet another mismanaged U.S. weapons program exhibiting the chronic flaws of a procurement system distorted by perverse vendor incentives and failed governmental oversight. The Secretary of Defense should immediately order changes to the Sentinel missile program to utilize the current Minuteman launch infrastructure, with minimal required modifications of existing facilities. Since no silos can survive attack by modern ICBMs, building new silos would greatly inflate the cost of the program while adding little operational capability. The willingness of the current Defense Secretary to make these changes will be a test of the Trump administration’s seriousness in eliminating waste in government operations. If the Defense Department does not act to contain the cost of this program, Congress should make continued funding contingent on implementing a sound design approach based on an independent review by experts outside the influence of the Pentagon and the contractor. Northrup Grumman should heed some common sense advice: If you find yourself in a hole, stop digging.