By Lambert Strether of Corrente

This hasty and improvisational post is, I hope, a bit of a palate cleanser from the election, the genocide, the drones, the liquid cats, and all the rest. I saw this wonderful post the other day on the Twitter and amazingly it had gone viral:

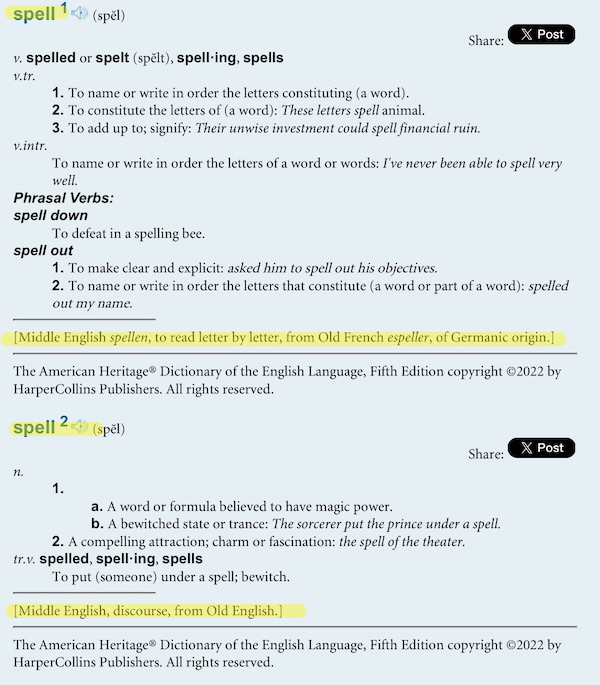

The thread impelled me to find out of “spell” (as in spells) and “spell” (as in spelling) were originally one word, or at least stemmed from the same root, but sadly, no. From the American Heritage Dictionary (AHD, of which more later):

Then again, at least in Ursula LeGuin’s Earthsea, a wizard has power over a thing when they know its true name — especially when they know not to use that power — and how can you know a true name if you can’t spell it? LeGuin’s dictionary was the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), although as we see, there are various brand spin-offs (Compact, Shorter, etc.):

All my life I have written, and all my life I have (without conscious decision) avoided reading how-to-write things. The Shorter Oxford Dictionary and Follett’s and Fowler’s manuals of usage are my entire arsenal of tools.*

* Note (1989). I use Fowler and Follett rarely now, finding them authoritarian. Strunk and White’s Elements of Style, corrected and supplemented by Miller and Swift’s Words and Women, are my road-atlas to English, and have never led me astray. A secondhand copy of the smallprint Oxford English Dictionary in volumes has been an infinite source of learning and pleasure, but the Shorter Oxford is still good for a quick fix.

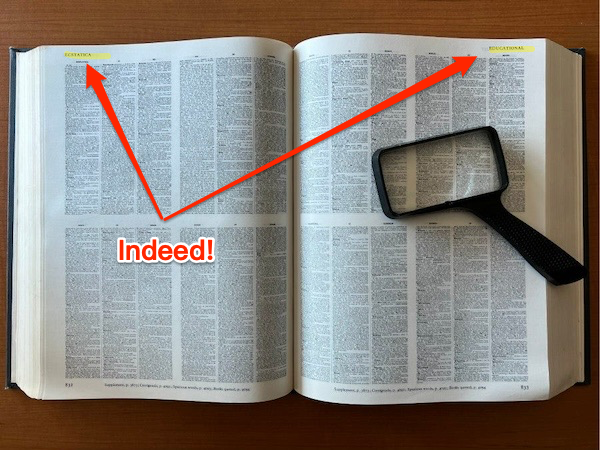

In any case, the seven-year-old girl received an OED. What a gift! I got my OED when I was a good deal older (though my mother did read to me from the Encyclopedia volumes we picked up every week at the A&P). I was working in the mills of Providence, RI at the time, and I ordered my OED from the Book of the Month Club. The pages looked like this, which is why it came with a magnifying glass (though I did learn to squint):

The OED, I thought, would be useful to me in my vocation as an adult poet, though I discovered too late I had nothing to say, at that age, in that medium. Nevertheless, I lugged it about with me until I lost it with the first of my lost book collections.

At some point between the mills and the advent of the personal computer, I discovered Raymond Williams, who made much better use of his encounter with the OED than I did. From his book Keywords, page 13:

Then one day in the basement of the Public Library at Seaford, where we had gone to live, I looked up culture, almost casually, in one of the thirteen [now twenty (!!)] volumes of what we now usually call the OED: the Oxford New English Dictionary on Historical Principles.

“Historical principles” means in practice that there are usage examples throughout (gathered by “correspondents” practicing, I suppose, “citizen etymology,” in an accumulative social structure much like that we have just seen at the Macauley Library). Williams goes on:

It was like a shock of recognition. The changes of sense I had been trying to understand had begun in English, it seemed, in the early nineteenth century. The connections I had sensed with class and art, with industry and democracy, took on, in the language, not only an intellectual but an historical shape…. [T]his was the moment at which an inquiry which had begun in trying to understand several urgent contemporary problems – problems quite literally of understanding my immediate world – achieved a particular shape in trying to understand a tradition. This was the work which, completed in 1956, became my book Culture and Society

Following Culture and Society, Williams went on to write Keywords. From page 14, the following convention:

Quotations followed by a name and date only, or a date only, are from examples cited in OED.

An example of the convention, from page 50:

CAPITALIST as a noun is a little older; Arthur Young used it, in his journal of Travels in France (1792), but relatively loosely: ‘moneyed men, or capitalists’. Coleridge used it in the developed sense – ‘capitalists . . . having labour at demand’ – in Tahletalk (1823).

So who knows what that seven-year-old girl will end up doing!

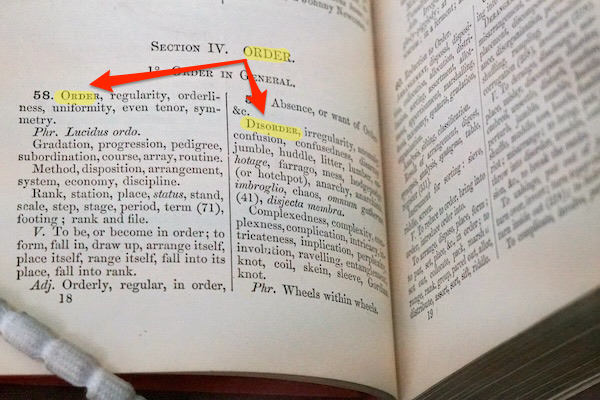

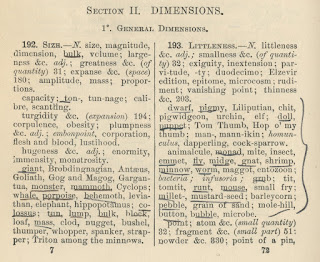

However, my very first reference work — I was a teenage poet, and did have things to say, at that age — was (image via James Moss) a Roget’s Thesaurus, the kind that we now see as old-fashioned. It looked like this:

As you can see, Roget’s organizes words into classes (“Order” is #IV of six). Within each class, opposing concepts are placed, well, opposite each other; as we see, Order vs. Disorder, or “progression,” “pedigree”, “economy,” and “station” are on the left, and the sinister “irregularity,” “huddle,” “farrago,” and “disjecta membra” are on the other. Quite unlike Newspeak, where “‘un–’ is used to indicate negation, as Newspeak has no non-political antonyms.” Now, of course, I’ve forgotten all those youthful follies, but the pleasure of looking from left to right for an opposite that is not quite opposite — is “complexity” really the opposite of “regular”? — and turning each word over in my fingers remains.

Sylvia Plath — an actual, adult poet — had used a Roget’s (image via Peter K. Steinberg), so I went looking, and found (image via Peter K. Steinberg) it had been sold at auction (“Lot 309”). Here it is, complete with her underlining:

(A mystery: Moss uses the same page at Steinberg — “order vs. disorder” — but doesn’t mention Plath. Why?)

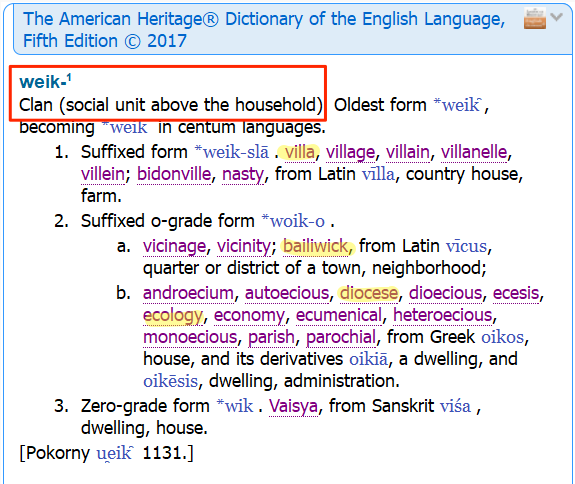

One more: Shortly after I discovered Roget, I discovered the AHD Dictionary of Indo-European Roots:

Fascinating that “villa,” “bailiwick,” “diocese”, and “ecology” (!!) all branch out from the same root. Endless forms most beautiful!

The complex data structures in all these works — historical principles (OED), classification systems (Roget), tree structures (AHD) may not have inspired great poety in me, but they certainly prepared me for a life of symbol manipulation, as the PMC manqué that I am!

Concluding, I highly recommend that you give the seven-year-olds in your life — as well as the poets, the wannabe poets, the autodidacts, or simply those who want to master the wondrous English language — reference works like the Oxford English Dictionary. And not the online versions, which are dumbed down, hard to use, and track you. Get physical, durable, endurable books. Go to a second-hand bookstore and get books, the older the better. Maybe you’ll hit the jackpot and find all twenty volumes of a full-size OED!