By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

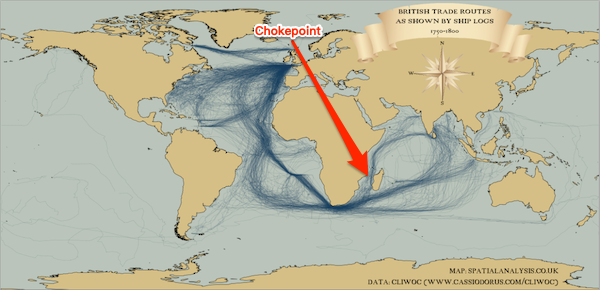

Everybody knows what chokepoints are — think a robber baron stretching a chain across the Rhine to collect tolls — but nobody seems to have noticed how ubiquitous the checkpoint concept is, or in how many contexts it appears. I wish this post could be a unified theory of chokepoints, but it’s not. (If collecting material automagically produced a theory, I’d be golden, but it doesn’t, not even with AI). Instead, I hope readers will indulge me in my passion for maps. There are probably contractors The Blob laying out maps of global chokepoints for wargaming even as you read now!

Maritime chokepoints are top-of-mind for most people — I have to add “-maritime” to my searches to get decent results — so I will cover maritime chokepoints first. Then I will define the chokepoint concept to make clear how broad the concept really is. There are two ways of looking at chokepoints: As nodes in a network (pipelines, undersea cables, the supply chain, and traffic flows) and as standalone nodes (food, weaponry, technology). After that I will consider how chokepoints are affected by their environment, and how multiple chokepoints can be layered in the same face (Egypt, the Persian Gulf). I will concluded with a brief note on “chokepoint capitalism” (back to the robber barons!).

I hope this superficial review of various types of global chokepoints will infuse your reading with new insights, and perhaps in a few inspire thoughts of how actual choking might be instantiated. To maritime chokepoints–

Maritime Chokepoints

From Phys.org in 2022, “New analysis maps out impacts of marine chokepoint closures“:

Cargo ships move about 80% of all international trade by volume and about 70% of it by value. Much of this trade passes through one or more marine en route to its destination. Pratson estimates that value of trade through a number of these chokepoints, such as the Malacca Strait and South China Sea, rivals the GDPs of the world’s largest economies.

Furthermore, some chokepoints, such as the Danish Straits, Bosporus Strait, Strait of Hormuz, East China Sea, and South China Sea, provide the only access to maritime trade for a large number of countries.

If these chokepoints are shut down or if traffic through them is reduced for a prolonged period, as has happened in the Bosporus Strait during the war in Ukraine, the disruption can block or severely limit affected countries’ ability to import or export goods their economies and world markets alike depend on. This can cause volatility in global supplies and prices and spur a scramble by nations and businesses on both sides of the chokepoint to secure alternative sources or markets for critical goods.

Here is an example the shows intuitively what happens to one maritime chokepoint — the Red Sea — during a war:

How the world changed in 10 days

A time-lapse visualizing the Houthi blockade at Red Sea chokepoint. pic.twitter.com/D3E582scEf

— Prop. co (@propandco) January 1, 2024

I suppose if I were in the business of writing clever headlines, I’d try: “From Chokepoint to Flashpoint. More seriously, from National Geographic, “This small strait is essential to global shipping. Now it’s the center of headlines“:

The Bab el Mandeb is a small geographical in the Red Sea with an outsized influence on world affairs: It’s the key to the control of almost all shipping between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea via the Suez Canal. Recent drone attacks on commercial shipping in the Bab el Mandeb by Yemen-based Houthi forces have prompted a coalition led by the United States to launch military strikes against targets controlled by the militants. And while the Bab el Mandeb is currently making headlines, it’s also played an outsized role in human history—here’s what you should know.

Like so many maritime chokepoints, it’s a narrow strait, and therefore hazardous:

The name Bab el Mandeb means “Gate of Tears” or “Gate of Grief” in Arabic, from “bab” meaning “gate” and “mandeb” (or “mandab”) meaning “lamentation.”

Its name appears to refer to the perils of navigating the narrow waterway, which is rife with crosscurrents, unpredictable winds, reefs, and shoals. Many ships in past centuries and millennia wrecked in the Bab el Mandeb, and modern ships also face the dangers of naval mines from bygone conflicts.

Here are three examples of maritime chokepoints represented as maps, by Chatham House, the Visual Capitalist, and the Boston Consulting Group. You will note subtle differences between them, showing the flexibility of the concept:

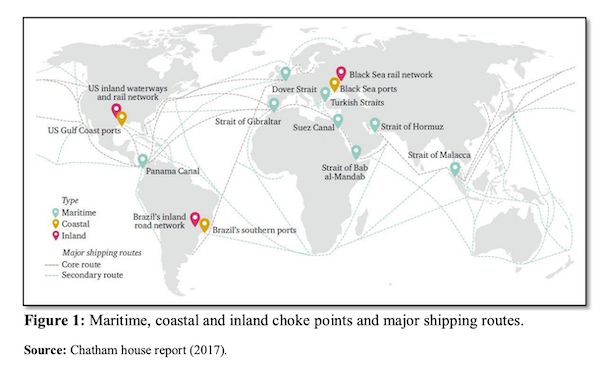

From Chatham House (2017), “Chokepoints and Vulnerabilities in Global Food Trade“:

International trade in [food] commodities is growing, increasing pressure on a small number of ‘‘ – critical junctures on transport routes through which exceptional volumes of trade pass. Three principal kinds of chokepoint are critical to global food security: maritime corridors such as straits and canals; coastal infrastructure in major crop-exporting regions; and inland transport infrastructure in major crop-exporting regions.

And the map:

The map does indeed represent not only maritime corridors, but types coastal and inland infrastructure. (Food, however, not represented as a chokepoint, although that’s a possibility, as we shall see.)

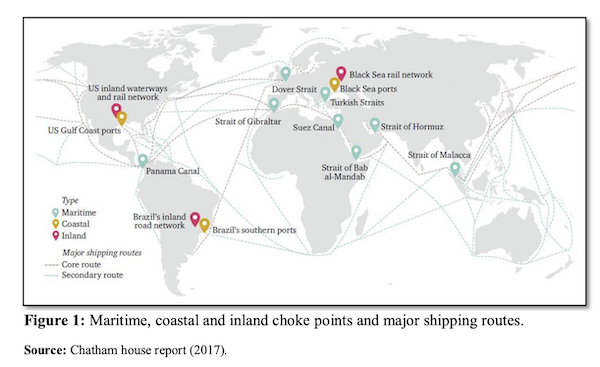

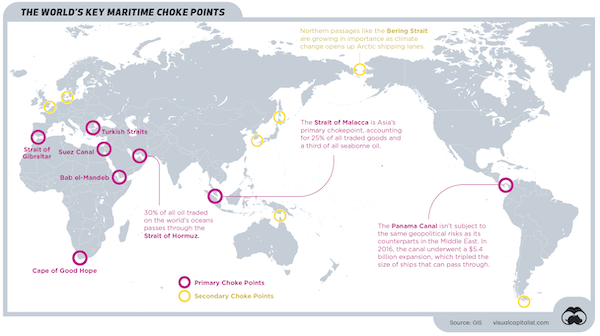

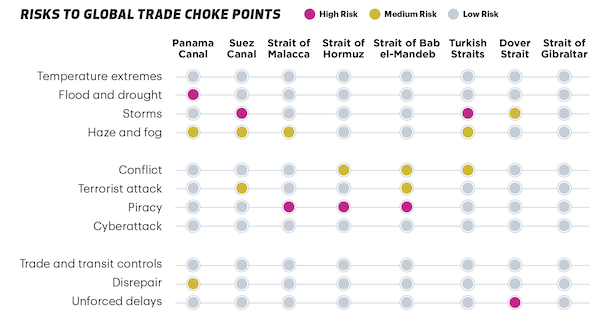

From the Visual Capitalist (2021), “Mapping the World’s Key Maritime Choke Points“:

Visual Capitalist’s map does not represent coastal and inland infrastructure; they do, however, have explanatory captions. They also have a handy chart of risks in maritime chokepoints.

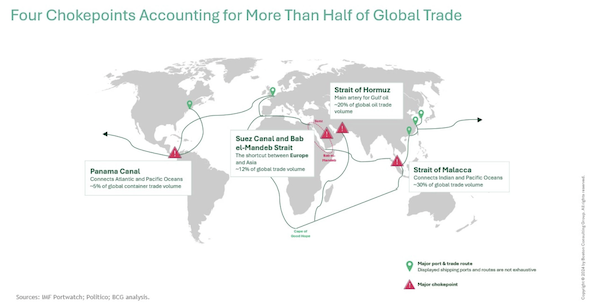

Finally, the Boston Consulting Group (2024), “These Four Chokepoints Are Threatening Global Trade“:

Right now, more than 50% of global maritime trade is at threat of disruption in four key areas of the world.

While the conflict in the Red Sea has been high in the news agenda, there are three other maritime passageways that risk becoming due to either geopolitical or environmental factors.

I would say that a chokepoint does not “become” but is, and there are more than four. Here is the BCG map:

BGG’s map differs from the other two in that routes are captioned as well as chokepoints.

Chokepoint Defined

Here are three more formal definitions. From LIMN:

A chokepoint is a narrow corridor, . Chokepoints are parts of a system that threaten to become a site of congestion or blockage, where movement might be stopped with very little effort. The network is often imagined as a form that routes around or bypasses chokepoints, but all networked systems still have at least one chokepoint. In most cases, they contain many bottlenecks, pressure points, and points of failure. This is true even for apparently distributed systems like the internet.

(“Restricts flow” like the robber baron. Or the Houthis.) Oxford Reference:

A point in a computer network through which all or most of the traffic in the network flows. Such points are vulnerable to both crackers and hardware failure. One of the main strategies of network designers is to minimize or eliminate the number of choke points.

And Wikipedia:

In military strategy, a choke point (or chokepoint), or sometimes bottleneck, is a geographical feature on land such as a valley, defile or bridge, or maritime passage through a critical waterway such as a strait, which an armed force is forced to pass through in order to reach its objective, sometimes on a substantially narrowed front and therefore greatly decreasing its combat effectiveness by making it harder to bring superior numbers to bear.

To me, all these definitions describe the same network structure, just in different fields using different terms. Now let us look at several networks besides maritime checkpoints.

Chokepoints as Networks

Here are several self-explanatory examples and maps.

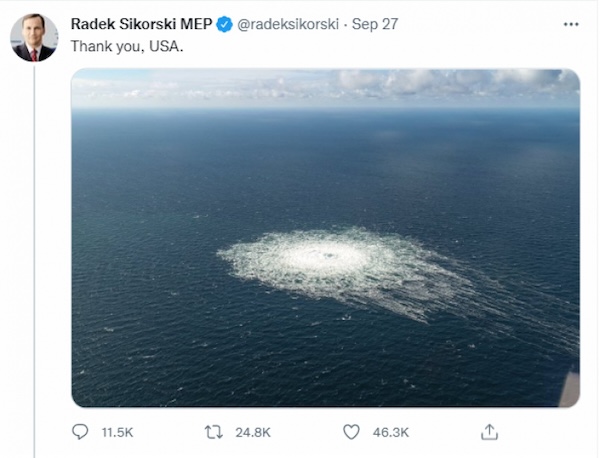

Pipeline chokepoint:

(You have to imagine the network of this is node is a (terminating) part.)

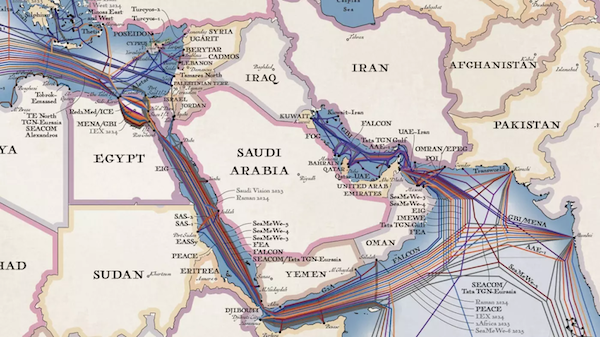

Undersea Cable chokepoints. From LIMN:

Our undersea cable system forms the backbone of the global internet. The most frequently discussed and debated in this system are geopolitical chokepoints. For example, if one looks at the map of the undersea cable system, it’s easy to locate where cable routes funnel through narrow geographic zones. These include the Strait of Malacca (between Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia), the Strait of Luzon (between Taiwan and the Philippines), and the crossing of Egypt and the Red Sea. At each of these points, cable traffic is rendered vulnerable not only because of geographic constraints (e.g. a canal, submarine topography), but also political constraints (including both national, territorial, and oceanic politics) that make it difficult to route elsewhere. Forced along a narrow path, cables often are subject to an increased threat of anchors, subsea movements, and nations and companies that control the space.

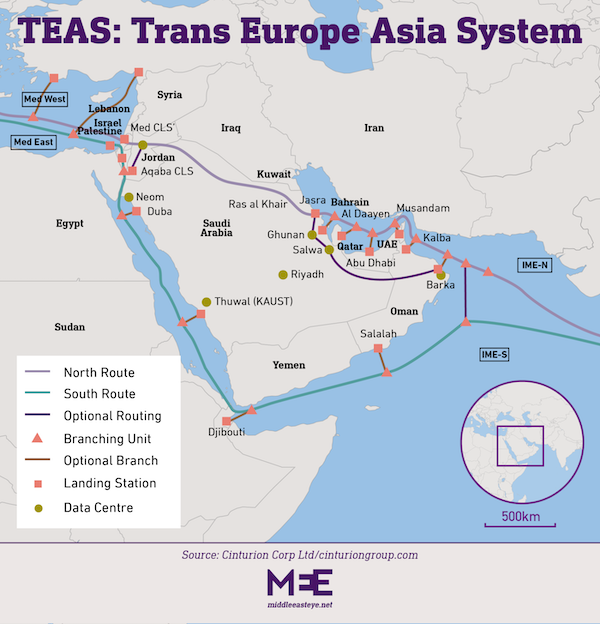

Here is an example of the Saudis strategizing on how to avoid cable chokepoints with cables on land, and not sea. From Middle East Eye, “How Saudi Arabia is redrawing the map of the future with fibre-optic cables“, the current map:

And the new map:

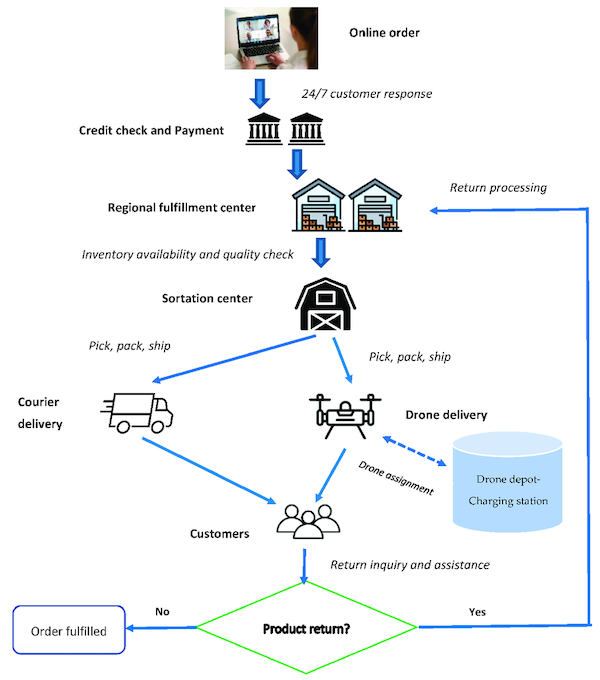

Supply chain chokepoints. From ResearchGate, “Leveraging Drone Technology for Last-Mile Deliveries in the e-Tailing Ecosystem“:

Yes, the sortation center is a chokepoint. So is the credit check (especially if that network goes down).

Somewhat farther afield, but showing once again the flexibility of the concept, traffic chokepoints. From Human Transit, “Chokepoints as Traffic Meters and Transit Opportunities,” No map (sorry), only prose:

The lesson of Seattle is that successful transit infrastructure responds to demand, and what drives transit demand is high overall travel demand plus serious barriers to driving. In Seattle, a lot of the barriers to driving take the form of hassle and delay, due to limited capacity through

Seattle’s advantage, in short, is a natural scarcity of transport routes, which is the same as an abundance of chokepoints. Because of this geography, even in the era when we were building roads everywhere, it just wasn’t possible to build an oversupply of roads connecting the various parts of Seattle. So transit’s advantage remains.

Effective transit infrastructure aims for the chokepoints, and seeks an advantage there. This is part of why various forms of Bus Rapid Transit have particular potential in Seattle: if you give transit an advantage through the chokepoint, you can achieve a lot of mode shift. The bus services across Lake Washington (between Seattle and its eastern suburbs) on I-90 do well because they have preferential access through a major chokepoint.

Chokepoints as Nodes (Network Implied)

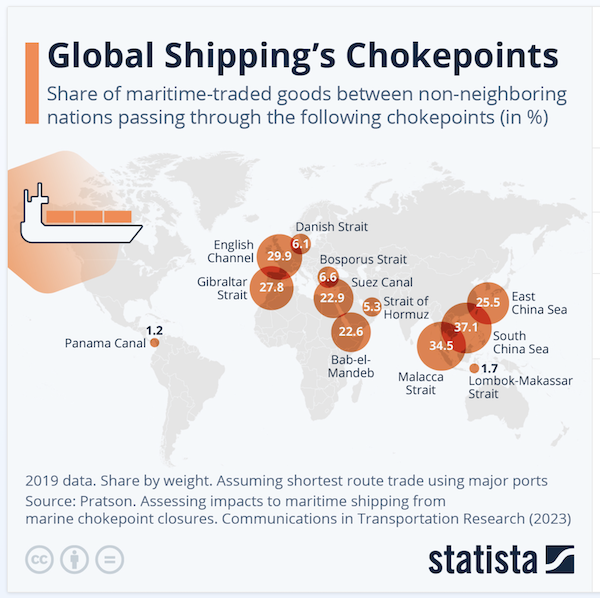

Here is an map that only shows shipping volume at any given node, living the network implied. From Statista, “Global Shipping’s Chokepoints“:

Here is a chart that takes the same approach, for weaponry:

Excellent. They may have (had) 150,000 missiles, but the LAUNCHERS are a crucial chokepoint. https://t.co/8f1eLCsidU

— Mitzi Rimon (@MitziRimon) August 25, 2024

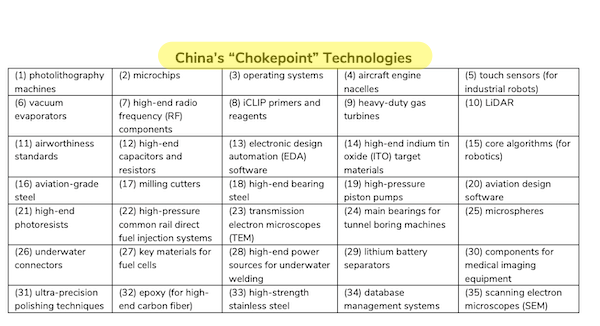

Here is a chart that takes the same approach, but for technologies. From the Center for Security and Emerging Technologies (PDF), “Summary of Chokepoints: China’s Self-Identified Strategic Technology Import Dependencies“:

One again we see the flexibility of the concept.

Influencing Chokepoints

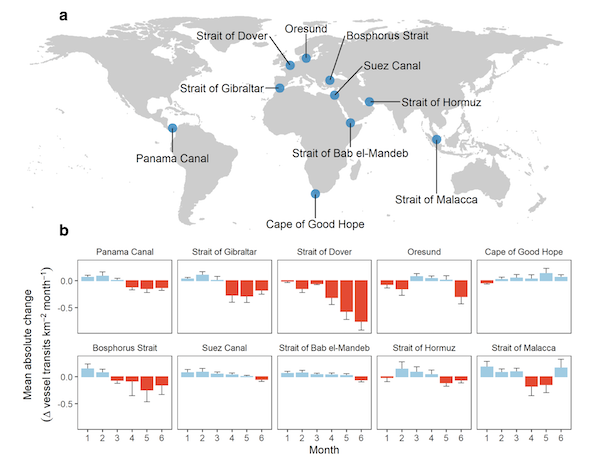

Chokepoints can be affected by their environment. From Nature, “Tracking the global reduction of marine traffic during the COVID-19 pandemic“, a chart (chokepoints marked in blue):

New chokepoints can also affect old chokepoints. An interesting historical example from Mozambique from the Center for International Maritime Security:

Then came Suez:

The Suez Canal, opened on 17 November 1869, drastically reduced shipping times and costs for trade between Asia, Europe, and the Americas. This ended the Mozambique Channel’s longstanding and central function as the indispensable link between Asia and the West, relegating it to a supporting role.

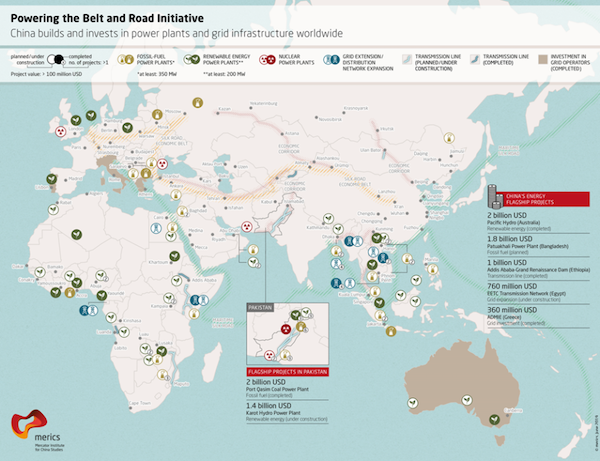

A more contempary example would be China’s Belt and Road initiative. From Rising Powers, “Ten Maps to Explain Climate Change and Geopolitics“:

One might regard Belt and Road as an enormous attempt to circument the maritime chokepoints set up by the West with a new network of chokepoints, but land-based.

Conclusion

It may be that the chokepoint concept is coming into its own, for good for ill. From the Financial Times (2024), “Charting trade chokepoints: a how-to guide“:

Last year, the commerce department launched a Supply Chain Center, to work with private sector partners on supply chain mapping. It has now begun quietly trialing a supply chain exposure tool that crunches trade and customs data from the US and many of its allies to create a detailed picture of where risks and opportunities lie.

The idea is to figure out how healthy — or not — these countries really are when it comes to supply chains in a variety of sectors, such as semiconductors, critical minerals, consumer electronics and so on. How quickly could critical inputs be replaced from allies in case of war, a pandemic or a natural disaster? How much do they depend on others from a single nation, such as China or Russia?

“We wanted to create a common operating picture and shared set of facts for supply chain discussions with allies in Europe or nations that are part of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework,” says assistant secretary of commerce for industry and analysis Grant Harris, who created the new centre. “Our baseline for those discussions too often had been, ‘we should all do more,’ and then things would stall, because we didn’t have the data for a more detailed conversation.”

It sounds like a no-brainer, but as someone who’s been concerned with supply chains since the Rana Plaza factory collapse in Bangladesh in 2013, this is the most granular US government effort that I’ve seen so far to map global in a broad range of commercial sectors. (I’d caveat this by noting that the departments of defence and energy have their own efforts targeted to their specific areas of interest.) According to several supply chain experts I spoke to, no other nation — apart from China — is doing more in terms of such cross-border mapping.

Meanwhile, very much outside the Commerce Department, we have the concept of “Chokepoint Capitalism”:

Chokepoint capitalism. @doctorow https://t.co/xMJtYTV4Dc

— DosGoats (@dosgoatsfilms) August 12, 2024

And those of you who considering internal expatriation might do well to consider where the next chokepoints might be:

Meanwhile, this ‘realness’ is situated along the St. Lawrence Seaway – the navigational chokepoint between the open ocean and 20% of the earth’s fresh water. Massena feels like a wise and sleeping giant – the forgotten land whose geography may again build an empire. pic.twitter.com/ZRO3YzjgK9

— 𝙷𝚒𝚌𝚔𝚖𝚊𝚗 (@shagbark_hick) October 18, 2022

Readers, more examples from your own encounters?