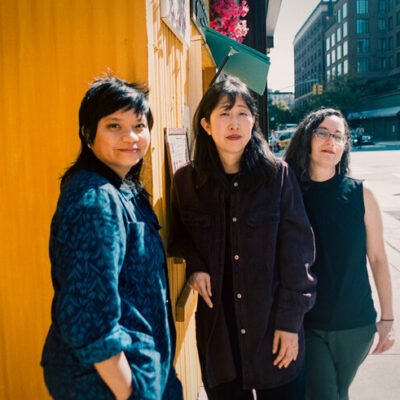

Marina Johnson: Salam Alaikum. Welcome to Kunafa and Shay, a podcast produced for HowlRound Theatre Commons, a free and open platform for theatremakers worldwide. Kunafa and Shay discusses and analyzes contemporary and historical Middle Eastern and North African, or MENA, and SWANA, or Southwest Asian North African, theatre from across the region. I’m Marina.

Nabra Nelson: And I’m Nabra.

Marina: And we’re your hosts.

Nabra: Our name Kunafa and Shay invites you into the discussion in the best way we know how, with complex and delicious sweets like kunafa, and perfectly warm tea, or in Arabic, shay.

Marina: Kunafa and Shay is a place to share experiences, ideas, and sometimes to engage with our differences. In each country in Arab world, you’ll find kunafa made differently. In that way, we also lean into the diversity, complexity, and robust flavors of MENA and SWANA theatre. We bring our own perspectives, research, and special guests in order to start a dialogue and encourage further learning and discussion.

Nabra: In our fourth season, we focus on classical and historical theatre, including discussions of traditional theatre forms and in-depth analysis of some of the oldest and most significant classical plays, from 1300 BC to the twentieth century.

Marina: Yalla, grab your tea. The shay is just right.

In this episode, we are joined by Fidaa Ataya, a Palestinian storyteller who talks with us about the tradition of the hakawati and how she and her work are looking at different forms of storytelling from ancient traditions to new ways of storytelling in Palestine.

Nabra: A quick bio, Fidaa Ataya is a storyteller. Her grandmother, forcibly expelled from her home and homeland in Al Bourj Palestine in 1948, would tell her stories. As she listened, Fidaa would fly with her imagination across borders, across the occupation, to freedom. Traditionally, women in Palestine told stories in private, not in public. But Fidaa tells stories in public, using them as a tool for survival, to pass on the anthropology of her people, to prove their existence and resistance.

She holds a bachelor’s degree in education and psychology, diplomas in drama and education and playback theatre, and an MEd in Integrated Arts from Plymouth State University [New Hampshire]. Fidaa has produced and performed shows in Palestine, Europe, America, and the Arab world and performed in numerous festivals across the globe.

Fidaa has founded or co-founded a number of groups including the Art and Activism Residency, Hakaya Group to revive traditional Palestinian storytelling, Arabic School of Playback, Women’s Theatre at Burj Al-Barajna refugee camp, the Rain Singer Theatre at Tulkarm refugee camp, and the Palestinian American Children’s Theatre (PACT), and heart Al Risan Art Museum (hARAM). She is a drama in education specialist and was faculty member at the Arab School of Playback Theatre, a member of ITC4 in New York, as well as a puppeteer, filmmaker, and director. She has directed several short films, which have been shown in Palestine, within the United States, France, and in Italy. With Seraj Libraries, she is running the National Storytelling Center in Palestine and teaching\directing the Storytelling Academy. As she is a fellow at Georgetown’s Laboratory for Global Performance and Politics, she continues to teach arts in education, arts in public, theatre, and storytelling in Palestine and abroad.

Since I am Palestinian, I think that this is my tool to exist and to be, to heal, to survive, and to be strong, and to root myself in order to grow and grow our stories all over the world.

Marina: Fidaa, it’s so good to have you with us today. I only got to meet you once briefly in person, but it was such a wonderful day where I got to join and see some of your storytelling marathon in Kafr ‘Aqab. Great to have you on the podcast.

Fidaa Ataya: Thank you so much, Marina as well Nabra for inviting me to join that storytelling.

Marina: Yes. Can you tell us a little bit about your journey into storytelling? How did you get involved in this as your project?

Fidaa: As a human being, every one of us has a tongue where we are really having the tool to storytelling. When I say tool, that means narrative. And then because since I am Palestinian, I think that this is my tool to exist and to be, to heal, to survive, and to be strong, and to root myself in order to grow and grow our stories all over the world. So I remember when I was child in early childhood when I was sitting on my grandmother’s lap and she used to tell me stories. With her stories, I could have just fly all over and cross our borders and even swim in the ocean as well, imagining something I never saw in my life.

And then from that inspiration I decided to become a storyteller in public. My grandmother used to tell stories in private. And this is who I am. I think that’s my journey started from there. My journey still… I don’t know for how long will stay, so I don’t know what to continue now and what to speak after.

Marina: That makes sense. What I love talking about like what our ancestors did and then also how we’re taking that up and doing something slightly different. When I saw you—I visited you at Seraj, the National Storytelling Center in Palestine this past summer—and that day you were doing the storytelling marathon, which I hadn’t heard of, and I think it was your own creation. Can you tell people listening a little bit about that project and what the kids were doing?

Fidaa: Yeah. First of all, Seraj Libraries established the National Storytelling Center. I joined them to establish that together in Kafr ‘Aqab old city, which is Area C, that means under Israeli military law, but owned by Palestinians for sure, which is like an old building, more than 150 years old, and has been forgotten for four years. We came and we renovated the location, the building, and we said, “Okay, let’s tell our stories through this place, and let’s share it all over Palestine and over abroad.” Seraj Libraries has started the storytelling marathon since years and years and the idea of it to work with three generations. First generation, the elders who have the stories, the narrative from their ancestors, and the second generation is the youth, anyone who’s from eighteen to fifty years old. And the third generation is teenagers who’s from twelve to sixteen years old. So the idea is that we train the mid-age people, that mean youth, to how they can collect kharareef from elders, mean old people in Palestine, and al kharareef mean folk tales. How to find the people who saved that history, how to listen to them, how to rewrite the story again as exactly it was told because this is a big responsibility since the folk tales as Professor Sharif Kanaana said, “That’s more than two thousand years old.”

So then the second step after they collect the stories, we train them to collect the story, they go collect the stories after they find the narrative, I mean, we call the natural storytellers. They come back and we choose all that. There is a committee for the storytelling marathon, choose the stories that has to be told in each location. Then we teach again back how you can tell the stories for the youth, and then they go back to the kids or teenagers, and they tell the story back to them, and then the kids learn the stories, and then they prepare themselves to tell the story back to the community or to the communities.

And the storytelling marathon this year was within ten partners, Jordan Valley, Kafr ‘Aqab, let’s say, and many other locations and was also in the Ramallah refugee camp, Aida refugee camp, South Hebron, and the Tubas. And in the end, all the kids start telling the stories in the same day and end after three hours. They go find the audience. The audience don’t come to them, they go to the audience. They knock doors. They go to shops. They tell in the streets, in hills, gardens. They go to schools. They go to universities and even falafel shop and even pharmacies, mechanics. And they tell the stories that… The child who tell the story more for more people that mean they are the winner.

As soon as you tell stories for bigger audience that mean that you are number one in storytelling. We got a child who told the story the same story who told the story for more than 1,200 people in three hours, and that’s a big number. We discovered that there is amazing, incredible child who tell a story in a very, very, very unique way during the marathon where we also gifted this person as well. And we discover amazing, incredible natural storyteller from south, from Jordan Valley who really have been saving a lot of stories from her ancestors. And this is how we honor them, to thank them, and to just gather with them, and listen to them, and share the stories to the community.

Back to performance. We do this consciously. So I designed with my team that the storytelling marathon consciously, and we were very careful about the type of stories they tell in the community and why, and when, and who telling the story now. So for example, let’s say in Kafr ‘Aqab we collected the story from elders that mean more than sixty years old. Then we teach it to volunteers who is mid-age. Then they tell it for young children, teenagers. Then the teenagers back to the community tell the story back to the community, whoever.

This is how we raise the Palestinian storytelling and how we raise the folk tales back. We shake it back in the middle of all of this occupation colonization and even media all over us in the middle of dust. We say we grow and we continue life.

Marina: I love that so much. I mean, I think some of the words that you’ve really touched on, too, of conscious, being really conscious about what stories you’re telling in a community, telling community stories back into that community. This intergenerational exchange of getting stories from your elders and then giving them into the community, that’s all so beautiful. So I just really appreciated getting to see part of this project and to know that this has been happening for a while and that this is something that’s happening in multiple communities.

I mean, it just sounds like such a moving project. And when you’ve talked to Nabra and I a little bit before we started about the idea of planting seeds and actually what you just described to me sounds a lot like planting seeds in different places, but you were talking about it in relation to some of the work you’ve done. So for instance, you co-founded Hakaya with some other folks, and perhaps you can tell us what that group does, but I know that you have also worked and started other groups too. So perhaps you can give us a little bit of an introduction into some of those groups and then also how you see your role in once something is established going to the next meaningful project to begin something new.

Fidaa: So I met Hakaya Group, they were in the first beginning of that was in Amman when I was performing and taking also to courses in storytelling as well during the festival they do organize with the Masrah Al Balad and the Arabic Educational Forum. I kept continuing performing and taking courses and learning from that festival for nine years in a row behind after, after, after for nine years.

Then during those nine years when I saw I was part of Hakaya Jordan, then I said, “Oh, why not we have Hakaya Palestine in Palestine?” I did not have the only one who have that thought. There was also other people who have the similar thought. Then we just gathered together, and we established Hakaya Palestine, and we create the first Hakaya Festival. And then Arabic Educational Forum suggested that if you would love to be under their umbrella, and we said, “Okay, we can do that.”

And after that I felt that there is an umbrella, and I don’t think I would love to continue in a deep core of this group because there is other people who can lead and take over. And I start to fade up to seed other places or to plant seeds somewhere else. Since I love also to grow the storytelling like a mushroom, not only like a tree. Because to be a tree and to grow deep, deep, deep, it’s not enough. You have to grow as mushroom as extend as much as you can because you still under threat, and you even under this occupation colonization where you don’t know when that will end.

And then I—with other amazing incredible people, partners, artists from Palestine and all over the world—we established a lot of groups like musical theatre and Rain Singer Theatre and storytelling groups, Kharareef, storytelling group, kan ya makan [once upon a time], and art and activism residency which based on the real stories from the communities who’s really living under direct occupation colonization as well as heart Al Risan Art Museum, which we tell the story visually about what’s going on in such areas, forbidden areas, like areas we are not allowed to be in as Palestinians because of the threat from occupation, colonization. And other, other, other things like we still continuing. And I think that we have to continue growing deep and extend that widely all over through storytelling in the way maybe that is the only way to be and live and to have our freedom.

Marina: That’s so meaningful. And for people who are listening too, I think sometimes in the United States we talk about decolonizing theatre and decolonizing different things. So using decolonization in some ways as a metaphor. And what I love about what you just described though is that it’s really decentralizing. So it’s not just giving all the power and agency to one organization and trying to funnel everybody into that organization by starting different things.

I mean, I love the idea of mushrooming out, but then you’re creating different groups who are able to be responsive to their communities and not just one large centralized organization, which is sometimes what happens with creative processes in the United States, and I think people are really working to try to change that, but I just love this as a decolonial approach. It doesn’t have to be everyone trying to own this one organization. It’s really about the collective and what the collective needs and creating different organizations to meet those needs. So that’s just so beautiful.

Nabra: And it also resonates with me with the entire core of oral tradition and storytelling that it is a decentralized mode of art. And everything you’re talking about when it comes to preservation of oral tradition is really resonant. Could you also specifically talk about the hakawati in Palestine? I know you’ve been talking about it in some different ways, but especially for people who don’t know what hakawati is, can you tell us more about that, how it relates to the storytelling that you do and teach and how similar your storytelling might be to a traditional hakawati?

I love also to grow the storytelling like a mushroom, not only like a tree. Because to be a tree and to grow deep, deep, deep, it’s not enough. You have to grow as mushroom as extend as much as you can because you still under threat.

Fidaa: I count hakawati as one way of storytelling techniques as well we have a lot of techniques in storytelling. So the art of storytelling is a huge topic where a hakawati is the Arabic version presented by a man who used to tell stories in the cafe, in the aeleyah, that mean on the roof, to other people that mean most of them, they were men then he used to have his own stories about war, heroes, fighting, solving problems. And other men used to hear and even divide to two teams like how we watch now sometimes people watch football and they go within either team and they chat and they go.

Then hakawati used to create this type of atmosphere where he divides also the audience to two teams. And this is the main storyteller. He’s presented by Adam. And who is Adam? Adam, everyone know him. And he even was… His story was written in holy books. Right? But what about Eve? Eve is the woman storyteller who is forgotten and no one even in profession told about her in history that much. And the only things we know about her that she is the wife of Adam. Why is that? I have no idea.

And this is I said about that women storyteller has to speak up and tell their stories in public and write that history through narrative all over. And then now we call this lady who tells that stories in public, hakawatia. Hakawati and hakawatia come from the verb of haki or haka mean someone who tells, speak or tells, haki or haka, yikhi, hkayat, then continue and grow to Hakaya, mean stories or tales, then become hakawati or hakawatia the person who practice and who really does that type of action, who’s telling that much then he is hakawati.

And the history did not speak about the women storyteller as hakawatia. They always used to call her M something, the mother of something, the mother this, the mother of Mohammed, the mother of George, the mother of what’s that make no sense when they ignore this amazing, incredible beautiful women who used to tell the stories as UNESCO when they count what hakaya mean in Palestine. They said Hakaya is the folk tales told by women. Women means the old load ladies in Palestine, and they call it kharareef as Sharif Kanaana mentioned in his encyclopedia with Nabil Alqam, they created five books which have I think between seven hundred to eight hundred Palestinian folk tales told by women. Sometimes Sharif Kanaana call them fairy tales. I think I call them wonder tales and folk tales back to little, tiny research.

Anyway, hakawati is a way of his storytelling. hakawati is another way of storytelling as well as we have another four ways. I have been digging deep in researching about those techniques. And the Seraj Library Storytelling Center produce a book and curriculum to teach those methods so to people who would love to be a storytellers in Palestine. And we have in the Storytelling Academy in partnership with Georgetown University and the Storytelling Center also in Rome, in order to create new generations of storytellers in Palestine and extend more and more professionally all over the world as well as we have another techniques in storytelling like sha’ir al-rababa the poet who have this rababa and instruments where he tells that poem and tell a story in the same time to people who used to be that person who passed news before the radio and the TVs that was this person sha’ir al-rababa who used to travel from a place to another to tell what’s happened to other community, to the next communities.

And people could learn about themselves and other people, other communities through that person. And he used to be a man as well. I don’t want to forget also–those ladies who used together in a circle and just sing specific songs and tell specific stories and wear black in a circle where is funeral and cry and do specific gestures in order to raise and memorize and even thank, or be sad, or be angry about this may be loss for the person who has died. And other more techniques as well.

So I think those are traditional Palestinian techniques has to be also learn and research. Someone has to research them more and more. Back to my researchers, no one wrote about those as techniques of storytelling. I think that we were the only first people who wrote about that on a book, and we are happy to have them to keep continue teaching this.

Marina: Yeah. I really want to see this book. Wow, inshallah in Palestine, inshallah, I’ll see you there this summer into the fall because I would love to see the book and just appreciate this really comprehensive overview you gave. And also sometimes I think people get really under the impression that storytelling has to look like “theatre,” but really the storytelling you’ve been talking about is people going into the community. They don’t have to be on stage in a spotlight, like women sitting in a circle wearing black and talking together.

These things that often people say like, “Oh, women are sitting and talking,” but it’s actually this really important way of continuing on traditions and passing on stories, especially in the instance as you were talking about where someone has died. So carrying on legacy through storytelling in this way. And I appreciated hearing. Besides Hakawati and Hakawatia, I don’t know the other techniques you’re talking about. So that’s really exciting research that you’re doing.

Nabra: Are there any other techniques that you want to just briefly mention? I know you talked about hakawati, hakawatia, sha’ir al-rababa, and nuwah. Are there any others that you can mention that the listeners can look up and learn more about in your book?

Fidaa: I think, yeah, for sure. We are now… The storytelling students taking a course of Box of Wonder, and that’s incredible technique where the storyteller have a box which have a lot of stories inside, and he also, he is a man in the tradition, I mean. Now I hope that there will be a lady who will hold this box and travel all over Palestine to tell stories. And bakawati, box of wonder, and shar al rababah. They used to earn money out of their profession as well nuwah, ladies who used to sing, tell stories in circle for a funeral that also that was in profession that mean they earn money in it.

But hakawatia, the women’s storyteller who used to tell stories in private, in her family house, extend house, she used to tell stories with that money because that’s part of her profession as mommy, as grand mommy, as a grand daddy, as an aunt, as just like family member. And she used to tell those stories in order to teach other ladies unconsciously and even to breathe, to breathe and to heal from maybe actions she had been living. As well, I will not burn the secrets because I’m still researching and searching about another three techniques. I will add them for another book, inshallah, and then I will keep that maybe for another broadcast to tell more.

Marina: That sounds perfect.

Nabra: All right. We’ll take the cliffhanger. That’s a great storytelling technique there that you’re using to bring us back and keep us engaged. So we’re very excited to hear about your research when it’s ready. But all of this is incredibly important to, as you’ve said, freedom and survival for culture and for people. And there’s so many, especially clearly female and feminist traditions that are really not talked about very often but are so integral to the culture.

So thank you so much for especially focusing on those traditions that are not talked about. It’s incredibly important work. And I was wondering what kinds of stories do you like to tell the most? Are there certain specific stories or topics that you especially like to focus on or even traditions that you especially find yourself in as a storyteller?

I do believe that stories I have been searching, looking, creating, writing, and performing did change me personally deeply in my core. So about that I do believe that I could change my audience and the people around me.

Fidaa: I think I’m a spontaneous in my life. I would love always to tell stories which come to my mind. I feel it in my heart and even my body, remembering some of it to share it within my audience, wherever is the audience is. I don’t have any specific stories or things. I always, always trust my experience in life and trust my traveling in Palestine, looking for natural storytellers and collect stories, hear from them, learn about their wisdom, and I just leave myself to improvise. A story will come on my stage to my audience.

Sometimes I do, for sure, create my performance within specific way and even very sensitive way, but that sometimes take between a month or even ten years to be on stage, the story I was listening to. That’s really such an experience to retell that story. It’s another story which is like to find the stories is a story. To curate the story again is another story. And to tell the story on stage for people, that’s another story. So I think I put myself in three different experiences and that mean the whole process is the experience for me. The whole process is the performance for me. The whole process is the learning, is the discovery, and that’s all we call it, how stories can change people.

So I do believe that stories I have been searching, looking, creating, writing, and performing did change me personally deeply in my core. So about that I do believe that I could change my audience and the people around me. And even not people, even stones, trees, nature around us. And even the energy all over us. We hope, and I personally hope that is the way to have our freedom and even to see the sun and the light for us Palestinians. It takes more, so much time, takes so much energy, take a huge number of people. But under this genocide where I think narrative is very important to keep sharing it and continue and continue.

Marina: Yes, and continuing. I love that. Well, as someone who works on many projects at a time, can you tell us what are you working on right now? What are the things that are filling your cup and your time?

Fidaa: Yeah. Now, I work within the tenth grade high school, Ramallah High School within the tenth grade, teaching them how they can tell stories. And we have the theme of Nakba that’s with Ramallah municipality. And back to that theme, the students have to collect and find stories where they do feel this is Nakba for them. You remember what’s Nakba?

Marina: Of course.

Fidaa: That was 1948. That’s an action we call when the Isr(aelis) came and expelled and kicked old Palestinians from their land in `48 next to the sea and here and there. And we become refugees all over Palestine and even outside Palestine. So I question the girls there, what does a Nakba mean for you? If Nakba finished or what? And all of them said, “No, Nakba continued, continuing and did not finish.”

They collected the stories to show me that Nakba is something did not finish, continuing until now. And they mentioned also the war, genocide war in Gaza and what’s happening in the West Bank of Palestine these days, the prisoners’ issues. And they mentioned the stealing land and apartheid war, and all the checkpoints they mentioned as well. The colonies settlements, Israeli settlements here and there. And they mentioned also as well for sure 1948 Nakba action and through stories they collected from others, also through real stories they live themselves in these days and even the stories they learn about their uncles and who was maybe murdered or in prison.

And those ladies, I worked with them, conduct them how they can tell the story back to the audience. We were rehearsing just like two days ago, and the performance will be performed on the stage of the theatre here in Ramallah City Center where the municipality in memorializing a Nakba Day. May 16, the performance will be.

And the second things I’m working on as well, opening the year, one of the Storytelling Academy. Now we have two classes, year one and year two. And year two we are in residence within the box of wonder, Adel Tartir who teach the students how they can create box of wonder and how they can learn that technique and use it if they want in their journey of storytelling. And year one also we are questioning, the students questioning themselves about who are they, why they are here in Palestine, what shall they do and which stories they should tell? Why, when, and what is their own vision in storytelling?

So we are developing those questions with them through the year and as well as we are also looking forward to work within… No, we will do, choose three stories within the British Council with the British council, choose three stories in the narrative and write that stories down in Arabic, then translate that stories to English and perform them Arabic-English and even use those stories in the Palestinian schools inside Palestine in partnership within the Ministry of Education. We are targeting the English teachers at school as well. We are targeting the storytelling academic students who will be able to perform in two languages and learn how they can do that.

As well as we are planning to open another two libraries within Seraj Library in two different locations within historical buildings, and we wish those libraries are the way to exist and archive, and share the stories of us Palestinians to each other. And there is also a lot of things we are doing right now, but I would not tell about every tiny things. But we also hARAM, heart Al Risan Art Museum. We started a new project in Gaza about Gaza, with a Gaza partner about collecting stories around before the war and now what people have been doing before October 7th and now what the same person doing.

It’s like to compare. It’s not about compare, just to feel the sense and to see the transition and to feel it, how life have been changing through that. As well as we are exhibiting now in this minute, heart Al Risan Art Museum exhibiting an exhibit part of Biannele Oregon in the United States. And we are like here believing that through this type of arts, this is the way to go. This is the way to resist and truths, and to strength, and even the way of being, or you have to speak up in different ways.

You can’t just choose one way and say, “Ah, we cannot do this.” As well as we are in the planning of creating a film about Palestinian prisoners, and we are creating the storyboard for the film documentary one. I just don’t want to continue because a lot of things we are doing, I’m doing with my colleague, friends, people, artists, internationals in Palestine, outside Palestine, and especially I’m making intensive work now here in Palestine within my Palestinian friends, people and colleague and artists.

Marina: Wow. Fidaa, you do so much. Whenever I was emailing you to ask you to be on the podcast, I was like, “I wonder if she even has time.” And it sounds like you really don’t, but we’re so grateful to get to talk with you because I mean hearing about some of these projects and we know it’s not all of the projects you’re working on, they’re just some of them. But so important that, yes, the Nakba is ongoing and to hear what students are bringing in stories from families, but also their own stories.

I mean, that’s so meaningful and important to gather these stories and to collect them and to hear them and to make sure that even the rocks are hearing the stories that these people are telling. And then also what you were just saying, this video about political prisoners. I have to say in the United States especially, and I know that you’re not just making it for people in the United States, you’re making it for people in Palestine, but there is such a lack of understanding of how many prisoners, Palestinians, are imprisoned, and I can’t imagine what it’s like to gather those stories.

But I can only say that for myself that I would be so not happy to hear them, but that they’re so important to hear because they’re so frequently left out of any narratives around Palestine. So how important that you’re gathering them and making this film that I do hope we’ll be able to all see sometime soon.

Fidaa: Yeah, I hope so. As well also, I directed two films. One is The Shepherdess. It’s about the presenting… Story about salt and sugar. And I metaphoric that story in the Jordan Valley where they have the salty river and the sweet spring, and I showed the lady that she…

Marina: Ooh, I don’t know about the salty river in the sweet spring. That sounds cool.

Fidaa: Yeah. Even the miracle is applied there in Jordan Valley. Jordan Valley is presenting like 30 percent of the West Bank and 88 percent of the Jordan Valley, it’s an Area C under Israeli military zone, and it’s the most beautiful place, magical place for me minimum in the world where we just feel something… The fruits there have another taste. The light there have another taste. The spring, even the spirit, even your body if you go there will feel different, which the Jordan Valley is under a big threat.

So about that, I created that film to just show the sweet and the salt of the place. The sweet presented by a lady who have been existing, they’re working hard between her kids, her sheep, and go to the mountain, creating fire, creating food, creating life and facing all this injustice and skeletons as well as challenges by not having district point, having this soldiers, having this sign, having this colony, having this, all that injustice around here. No water, no electricity, living in a tent all the time.

Her house has been demolished. It’s a short movie. And between documentary and imaginative as well as another… That film was produced by Shashat, and the second film, I Came, But I Did Not Arrive, that was produced by the Storytelling Center, which I also speak the story about a Palestinian musician who have been living a lot of life, hard life, started when he’s a refugee, Palestinian refugee living in… Was born in Lebanon, then he exit to Yemen, then to Syria, then back to Lebanon, then going back to Palestine with an Oslo. After Oslo, then Gaza, then now he back to the West Bank of Palestine, and he became a musician, a very beautiful musician who play accordion, keyboard and Darbuka and just like beautifully nicely, we tell the story without any word. Just only visually. And it’s a short movie as well. Those are cinema movies. Maybe you can find the trailer here and there, but I wish we can show them here and there as well, more and more.

Nabra: Well, we want to see all of your work more and everywhere. It’s important to the whole world, and really lovely to speak to you about especially how you are connecting these traditional stories to the present day and talking about the future. Through that you’ve really found this way to capture storytelling, capture and preserve the traditional storytelling, but really move it into the future, especially with work with young folks, but also in the ways that you are building new institutions and documenting, and writing books and making movies that can live on.

And especially in that continuation of oral tradition, which is so difficult to figure out how to do that in a way that’s really authentic and preserves the actual methodology of oral tradition. So it’s been really incredible to talk to you. Fidaa, we’ll be looking out for all of your work. We both want to read that book. And also we’ll be waiting to hear more about the other storytelling traditions that you’re still researching now. So thank you so much for being here on this podcast today. It was such a pleasure and an honor.