Early in the Covid pandemic, some economists thought to raise the issue of whether it might have a serious enough impact on the labor market so as to give workers more bargaining power against employers and so result in higher pay and improvement in condition. Experts almost universally dismissed that notion, pointing to the fact that Covid fatalities were nothing like that of the Black Death, which did produce a labor market reset, and the very bad Spanish flu had not had a lasting impact on wage rates.

That initial assessment is now looking a tad premature. No one (except those who recognized that there is no durable immunity to a coronavirus) then thought Covid would become a chronic, widely circulating disease that now also mutates a plenty. And no one (except those who knew the pathology of SARS-1) thought it would produce significant levels of lasting disability, in the form of Long Covid. The risk increases with each infection. A report by Statistique Canada showed that the risk of Long Covid was 38% with three infections. Studies in other countries suggest even greater incidence:

It’s not “my” model. This is data from StatCan and other sources clearly shown on the diagram.

However repeat covid infections is a cumulative effect. South Korea and some other countries are putting the impact of Long Covid considerably higher than 38%.

— Paul B | 💚💙 Reform democratic system of UK (@Paul_Briley) March 3, 2024

Lambert has taken up the labor market impact of Covid as a beat. We came up with little in the way of studies and asked an economist who has an encyclopediac knowledge of research and keeps up on new work. He said that this was not something economists were up on; Lambert would do better going to science and public health sources. So you can expect them to be laggards on this topic.

The work that Lambert nevertheless did find featured Long Covid prominently. From his initial foray:

In the previous round-up, I cited two studies. One estimated the total impact of the Covid pandemic at $14 trillion; the other estimated the impact of Long Covid at $3.7 trillion[4]. Today we have two additional studies on Long Covid, the first on disablity in the United States, the second on the labor participation rate in the EU.

1) “Long COVID Disability Burden in US Adults: YLDs and NIH Funding Relative to Other Conditions” (preprint) [medRxiv]. Data from the US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey (HPS) and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) /Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Long COVID Study Group:

Long COVID represents a mass disabling event of significant public health concern. Long COVID is associated with a 21% loss of health – comparable to traumatic brain injury or complete hearing loss. Among US adults, 5.3% reported having Long COVID in October 2023 and 1-in-4 with Long COVID consistently report significant activity limitations from its symptoms. Across the 12-month sample of n=757,580 US adults, 1.5% (n= 10,401) met our case definition of disabling Long COVID. Their estimated frequency of the population equates to 3,801,986 adults with long term symptoms after COVID that significantly limits daily activity.

(I would tend to equate disabled with being out of the labor market entirely.) 3,801,986 is a lot, especially considering that we’ll keep adding to the total, if current trends continue.

2) “Long COVID: A Tentative Assessment of Its Impact on Labour Market Participation & Potential Economic Effects in the EU” (PDF) [The European Commission].

To the best of our knowledge, so far, no study has explicitly addressed the impact of long COVID on the EU labour market. The present paper provides a tentative assessment using available estimates from surveys, clinical follow-up studies and model simulations of the prevalence of long COVID. This tentative approach yields an estimated prevalence of long COVID cases of around 1.7% of the EU population in 2021 and 2.9% in 2022, resulting in a negative impact on labour supply of 0.2-0.3% in 2021 and 0.3-0.5% in 2022. In person-equivalents, this means long COVID is assumed to have reduced labour supply by 364,000 – 663,000 in 2021 and by 621,000 – 1,112,000 in 2022 – combining the effect of lower productivity, higher sick leaves, lower hours, and increased unemployment or inactivity. … Available labour market data suggest a mixed picture when it comes to the impact of long COVID…. Other indicators suggest that in 2022, health-related issues (COVID-19-related or of other origin) contributed more than in previous years to a reduction in labour supply at the external (i.e. transition into inactivity) and the internal margin (i.e. a reduction in hours). Notably, there has been a sizeable increase in sick leave reported by several EU Member States in 2022, with acute COVID, long COVID and seasonal respiratory illnesses all likely to have been significant contributors. There has also been an increase in people reporting disability or longterm illness, people inactive due to illness or disability and in part-time work due to illness or disability. The timing and distribution of these observations (with women being more severely affected) could mean that long COVID is a contributing factor. Overall, the health impact of long COVID warrants careful monitoring.

2.9% * ~450 million (the EU population in 2022) = 13,050,000 people. That’s a lot, comparable to the 16 million (CDC) with Long Covid in the United States.

An end-of January Bloomberg report gave prominent play to the fact that German data showed that ongoing illness was creating a bigger economic drag than during the pandemic (notice Bloomberg drafted the piece to present Covid as over). From the story:

German officials insist their economy doesn’t merit the “sick man of Europe” label, but a new study suggests illness is really playing a part in its poor performance.

Gross domestic product would have risen 0.5% last year if it hadn’t been for work absences due to poor health — a tally that surpassed pandemic totals to reach a record in 2023, according to analysis by VFA, the country’s association of research-based pharmaceutical companies.

Some €26 billion ($28.2 billion) in real income was lost due to illnesses among employees — equivalent to about 0.8 percentage point of total output, economists Claus Michelsen and Simon Junker wrote in a report released on Friday. High levels of absences in November and December point to another hit in the current quarter too….If absences due to sickness recorded over the past two years were to become the new normal, the economy would lose the equivalent of 350,000 employees, the study showed. That tally is twice as much when also making up for some overtime and productivity improvements.

Now admittedly no where does Bloomberg, and one assumes the German officials, attribute the persistent increase in health-related absences to Covid. But despite cheery CDC’s and other public health officials’ near total silence on the matter of long-term harm from Covid infection (save now some acknowledgement of Long Covid), many studies have found evidence of direct and durable damage from Covid, including impairment of the immune system. And given the correlation in timing, it seems reasonable to think that Covid has a big role in Germans’ health decline.

Now to the Wall Street Journal article. It describes how “independent” restaurants, meaning non-chain eateries, are in a world of hurt due to rising costs and many are at risk of closure due to a terminal budget squeeze. A secondary cause is erratic traffic, which it depicts as a post-Covid effect (think for instance that work at home means fewer with set commutes on weekdays, which in turn has an impact of their restaurant patronage). I dimly recall an article years back (in one of the CA non-mainstream pubs?) describing how there were simply too many restaurants in the moderately-to-pricey-but-not-special-occasion/expense account category to survive, that a shakeout would come).

And restaurants are a difficult business to begin with. The hours and work pace are hard, and there is no way to lock in customers. It has low barriers to entry, so a successful-looking venture is vulnerable to new establishments winning over their patrons.

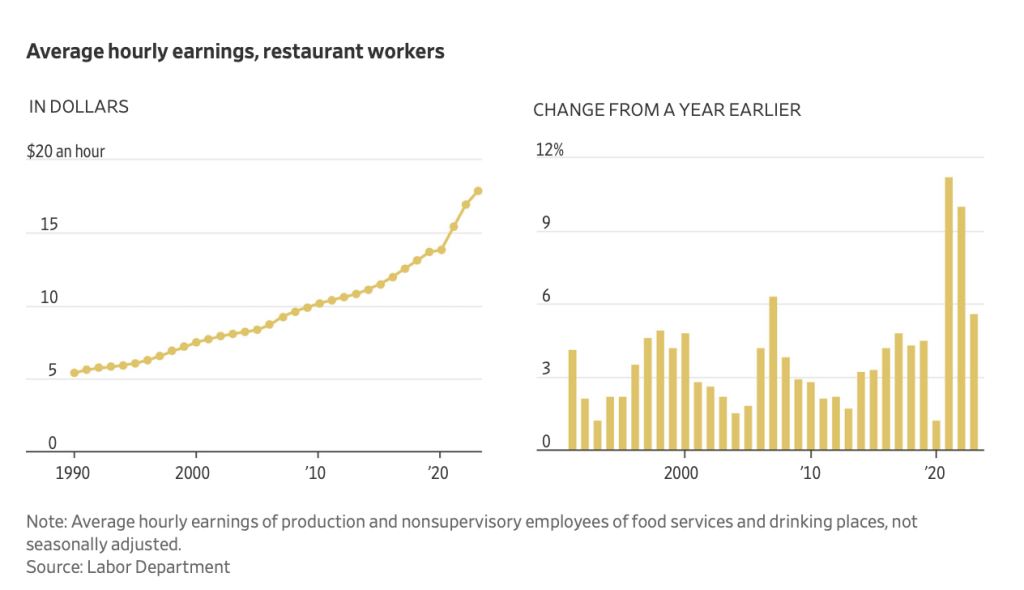

While the story weight heavily on rising expenses, for most dining spots, the biggest pressure is the rising cost of help. But oddly, they don’t connect the tight labor market, particularly for low-end workers, to Covid.

Let us consider what it takes to work in a restaurant. Pretty much every position requires a decent amount of physical stamina and executive function. You are on your feet for most of your shift. You have to juggle orders and deliveries to tables. Waitstaff have to deliver dishes to the person who ordered them. Even lowly busboys have a routine for table setup and clearing they need to follow.

Even though public health official and the press loath to connect persistent labor market tightness to Covid, the usual handwave, of attributing it to the baby boom cohort retiring, does not have much explanatory power for restaurant workers, who skew young. For instance, I recall one reader describing how his joint were ruined by 20+ years of being a cook. Notice how the Journal, at the top of the piece, identifies rising labor costs as the biggest pressure:

Independent restaurants are on financial life support, owners say, squeezed between escalating payroll costs and diners’ dwindling tolerance for ever-higher checks. Wages for waitstaff, table bussers and line cooks will grow more expensive for many eateries this year, with 22 states in January raising the minimum wage for hourly workers….

Restaurants’ food bills have stopped their pandemic-era surge. But payroll costs are still climbing.

In January, 59% of small-business owners reported higher labor costs were their biggest source of inflation, according to a survey of more than 425 entrepreneurs conducted for The Wall Street Journal by Vistage Worldwide, a business-coaching and peer-advisory firm….

As a percentage of sales, restaurants rely on labor more than other retail sectors, making the rise in wages particularly draining on profits, according to industry economists. It takes 12 employees to generate every $1 million in restaurant sales versus roughly three employees at grocery, general merchandise and clothing stores, according to analysis by the National Restaurant Association….

Labor costs have been rising faster and longer at independent restaurants than in the economy as a whole, with full-service restaurants seeing the biggest increases over the last year, according to an analysis by Gusto, a small-business payroll and benefits provider.

Again, one can correctly point out that minimum wage increases are long overdue. Obama in his first bid for the presidency promised to increase the Federal minimum wage to $9.50. It is still $7.25 (we’ll skip over the sub-minimum wage for restaurant workers; the point is the long duration of no increase for low-end work). So arguably, restaurants that depended on really cheap labor have been living on borrowed time.

But the reason minimum wage increases are sticking in so many state is not just due to inflation but also to businesses acquiescing, presumably because they can’t get enough adequate people at the current minimum wage anyhow.

The piece neglects to mention that one of the dining spots it showcases, Chef Zorba’s Restaurant, is in Colorado where the minimum wage has increased to $14.42 in 2024, up from $13.65 in 2023. Another is Johnny Roger’s BBQ & Burgers in North Carolina, where the minimum wage remains $7.25 an hour. Only for the third does it make explicit that the rise in pay costs have nothing to do with higher minimum wages:

Evan Kelamis, owner of breakfast and lunch spot Savoy in Tulsa, said his labor costs increased by more than 16% in 2023 alone—though the minimum wage in Tulsa has stayed at $7.25 per hour—because he has to pay more to attract and retain workers.

The Colorado restaurant reports having to improve benefits too:

In addition to minimum-wage increases, LuKanic now spends thousands of dollars a year for paid sick leave and other employee benefits. She said she’s increased salaries of her managers to around $65,000 a year to remain in line with her hourly workers’ additional pay.

Some longer term data:

There were also interesting tidbits that the article did not pursue, presumably due to the focus on the profit squeeze. For instance, the North Carolina restaurant saw its takeout business go from 20% pre-pandemic to 80% now. That’s a remarkable change. It would be nice to know if it is representative, since as the story points out, it does have a big operational impact. Sadly it is more likely due to diners having become habituated to eating at home, as opposed to Covid cautiousness.

It is not hard to imagine why the restaurant operators might not want to consider that Long Covid is contributing to their budget woes. They, like everyone in the hospitality and travel business, needs Covid to be over. They want the old normal back even if that will never occur. Thinking that Covid is still circulating and can (will!) further reduce their labor pool and make their workplace hazardous is not something they can entertain.

This long-ish piece does note in passing that the restaurant workers even in the relatively-well-remunerated Colorado eatery are having trouble making ends meet. So one could imagine that if worker scarcity persists, there will be yet more increases in pay at the low end of the scale.

Admittedly, Covid health effects and vanishing workers only a part, and a hidden part, of this particular picture. But the failure to manage this crisis better is already inflicting sizable costs on the economy, and it’s set to only get worse with Covid reinfections having a cumulative cost.

Like the war in Ukraine, the officialdom chose to rely on shock and awe, here of vaccines, and weren’t willing to pursue other measures seriously because that would have been real work, such as incurring costs (such as for distribution of high quality masks) and involved spending political capital (for instance, requiring better ventilation in schools and hospitals). And now we are seeing that over-reliance on a simple-seeming solution is producing serious blowback.