Researchers at the University of Southampton have found new evidence that Earth’s climate did not completely grind to a halt during its most extreme ice age, a time often called Snowball Earth.

This dramatic chapter unfolded during the Cryogenian Period, between 720 and 635 million years ago. Scientists have long thought that during this interval, the planet’s climate system essentially shut down.

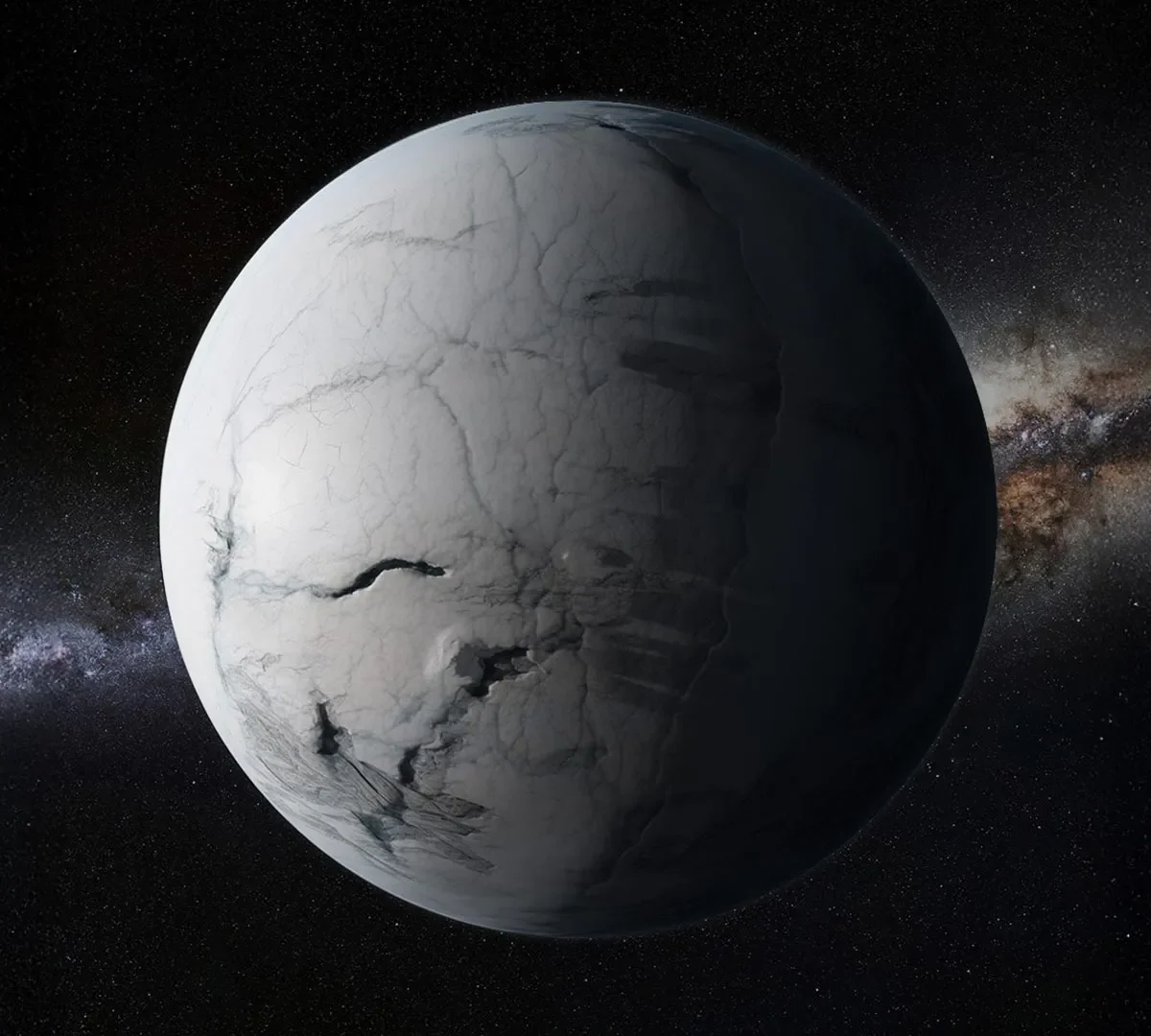

Massive ice sheets stretched all the way to the tropics, covering much of the globe in ice. From space, Earth may have looked like a giant snowball. Under these conditions, experts believed that exchanges between the atmosphere and oceans largely stopped, suppressing short term climate shifts for millions of years.

A new study published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters challenges that assumption. The research indicates that at least during one phase of Snowball Earth, the climate continued to fluctuate on yearly, decadal, and even century long timescales, with patterns resembling those seen in the modern climate system.

Scottish Varves Capture 57 Million Year Old Climate Record

The discovery is based on exceptionally well preserved layered rocks called varves on the Garvellach Islands off Scotland’s west coast. These sediments formed during the Sturtian glaciation, the most intense Snowball Earth episode, which lasted about 57 million years.

Thomas Gernon, Professor of Earth and Planetary Science at Southampton and a co author of the study, said: “These rocks preserve the full suite of climate rhythms we know from today — annual seasons, solar cycles, and interannual oscillations — all operating during a Snowball Earth. That’s jaw dropping. It tells us the climate system has an innate tendency to oscillate, even under extreme conditions, if given the slightest opportunity.”

The team closely analyzed 2,600 individual layers within the Port Askaig Formation. Each layer represents a single year of sediment buildup, offering a year by year archive of ancient climate conditions.

Lead author Dr. Chloe Griffin, Research Fellow in Earth Science at the University of Southampton, said: “These rocks are extraordinary. They act like a natural data logger, recording year-by-year changes in climate during one of the coldest periods in Earth’s history. Until now, we didn’t know whether climate variability at these timescales could exist during Snowball Earth, because no one had found a record like this from within the glaciation itself.”

Microscopic examination suggests the layers formed through seasonal freeze and thaw cycles in calm, deep waters beneath ice cover. When researchers applied statistical analysis to differences in layer thickness, they detected clear repeating patterns.

“We found clear evidence for repeating climate cycles operating every few years to decades,” said Dr. Griffin. “Some of these closely resemble modern climate patterns, such as El Niño-like oscillations and solar cycles.”

A Brief Pulse of Climate Activity in a Frozen World

Despite these findings, the researchers do not believe such variability defined the entire Snowball Earth period.

“Our results suggest that this kind of climate variability was the exception, rather than the rule,” explained Professor Gernon. “The background state of Snowball Earth was extremely cold and stable. What we’re seeing here is probably a short-lived disturbance, lasting thousands of years, against the backdrop of an otherwise deeply frozen planet.”

To better understand how this could happen, the team ran climate simulations of a frozen Earth. The models showed that if the oceans were completely sealed beneath ice, most climate oscillations would be suppressed. However, if even a small portion of the ocean surface, roughly 15 per cent, remained ice free, interactions between the atmosphere and ocean could resume.

Dr. Minmin Fu, Lecturer in Climate Science at the University of Southampton, who led the modeling work, said: “Our models showed that you don’t need vast open oceans. Even limited areas of open water in the tropics can allow climate modes similar to those we see today to operate, producing the kinds of signals recorded in the rocks.”

These results support the idea that Snowball Earth was not always entirely frozen. Instead, it may have been punctuated by intervals sometimes described as ‘slushball’ or more extensive ‘waterbelt’ states, when pockets of open ocean appeared.

Why Scotland’s Rock Record Matters

The Garvellach Islands site was key to reconstructing this ancient climate story.

Dr. Elias Rugen, Research Fellow at Southampton who has worked on the Garvellach Islands for the past five years, said: “These deposits are some of the best-preserved Snowball Earth rocks anywhere in the world. Through them, you’re able to read the climate history of a frozen planet, in this case one year at a time.”

Understanding how Earth’s climate behaved during Snowball Earth offers insights that extend far beyond this ancient era.

Professor Gernon said: “This work helps us understand how resilient, and how sensitive, the climate system really is. It shows that even in the most extreme conditions Earth has ever seen, the system could be kicked into motion. That has profound implications for how planets respond to major disturbances, including our own in the future.”

The study was supported by the WoodNext Foundation, a fund of a donor-advised fund program, whose support sustains Professor Gernon’s research group at the University of Southampton.